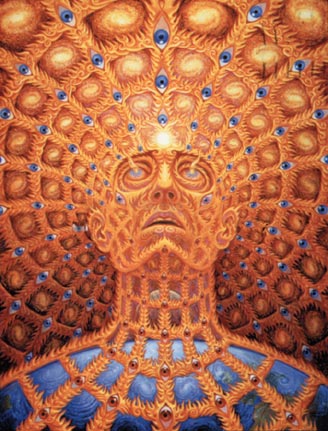

One of Hinduism’s best known bronze statues is that of Shiva Nataraja. Like the Buddha seated in meditation, or like Christ suffering on the cross, this image has become something of a religious icon. The product of a devotional movement that swept through the tenth century Chola Empire of Southern India (Harle 301), the statue depicts Shiva eternally creating and destroying the universe while dancing on the back of an ignorant ego. Although the statue itself is the product of a narrowly bound devotional Indian cult, the metaphor of Shiva’s dance is significant far beyond those bounds, having implications not only for art historians or religious scholars, but also for psychologists, anthropologists, physicists, and philosophers.

Shiva Nataraja was created as the result of exceedingly complex interactions between various social and religious movements. Hinduism before the Buddhist alternative was more technical and ritualistic than it is today. Between 788-820CE the non-dualist (advaitic) philosopher Shankara started a reformation that led to a highly philosophical but impersonal religious stance (Hopkins 119). After Shankara came Ramanuja in 1017 CE who further reformed non-dualist philosophy (Advaitic Vadanta) into a very personal and devotional stance. Ramanuja founded the “qualified non-dualist” school (Vishishta-Advaita) that gave rise to devotional Vaishnavism, (Feuerstein 241), a devotional movement centered on Krishna as a manifestation of Vishnu. However, this Vaishnava devotional movement affected its rival Shaivism. Under all this cultural and historical influence Shaivism became increasingly centered on the personal—but still non-dual—devotional experience, until eventually anonymous craftsmen began to create Shiva Nataraja statues as the centerpiece of their devotion.

Historically, the first statues of Shiva Nataraja coincide with the emergence of the early Chola Empire in 935CE (Goetz 258), an empire that formed on the south eastern tip of the Indian Subcontinent and whose worship of Shiva can be traced back to Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Valley Civilization circa 2300—1750 BCE (Harle 18). But, the bronze statues of Shiva Nataraja don’t appear until the early Chola and they don’t find their perfected form until the later Chola period. The prabhas or ring of fire is the clearest way to tell the Nataraja of the early Chola period from the Nataraja of the later, thirteenth century Chola Empire. In the early period the prabhas was shaped like an arch, while in the later period it was formed into a perfect circle (Harle 326). The difference is slight but the esthetic and psychological affect is great. Remember, these statues were placed inside temples and used as a focal point for contemplative devotion; the circle brings to that contemplation a greater sense of completion and wholeness.

The contemplative’s need for wholeness must be kept in mind as we look deeper into what Shiva is, psychologically, to the minds of his devotees. How does one find wholeness in Shiva, a super-natural being who lies outside the reaches of our natural bound senses? With this question, and with the need to look psychologically deeper, we can do no better than to retrace the footsteps of Joseph Campbell, as he in turn looked to Jung for help:

“If it were possible,” C. G. Jung has suggested, “to personify the unconscious, we might think of it as a collective human being combining the characteristics of both sexes, transcending youth and age, birth and death, and from having at its command a human experience of one or two million years, practically immortal. If such a being existed, it would be exalted above all temporal change; the present would mean neither more nor less to it than any year in the hundredth millennium before Christ; it would be a dreamer of age-old dreams and, owing to its immeasurable experience, an incomparable prognosticator. It would have lived countless times over again the life of the individual, the family, the tribe, and the nation, it would posses a living sense of the rhythm of growth, flowering, and decay.” (12)

From Jung’s words we can see that the devotion towards and the experience of Shiva is not to be directed or sought for either outside our “selves” nor outside our experience. Indeed, it is inside the experience of our selves that we must look for Shiva psychologically, i.e. with our intelligence, our emotions, our will, and our personalities. Leaving aside the question of how we come to experience Shiva for a later discussion, let’s take a closer look at Shiva Nataraja to see how we can come to this understanding of the artwork’s meaning.

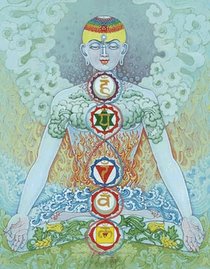

First, to help us understand the symbols employed by the craftsmen, are the words of Joseph Campbell as he describes the statue in The Mythic Image:

The upper right hand of the dancing god holds a little drum shaped like an hourglass, the rhythm of which is the world-creating beat of time, which draws a veil across the face of eternity, projecting temporality and thereby the temporal world. The extended left hand holds the flame of spiritual light that burns the veil away, thus annihilating the world and revealing the void of eternity. The second right hand is in the ‘fear-dispelling’ posture, and the second left, lifted across the chest, pointing to the raised left foot, is in a position known as ‘elephant hand,’ signifying ‘teaching’; for where an elephant has gone through jungles all animals can follow, and where a teacher leads the way disciple follow. The left foot, to which the ‘teaching hand’ points, is lifted to symbolize ‘release,’ while the right stamping on the back of a dwarf named ‘Forgetfulness’ drives souls into the vortex of rebirth. The dwarf is gazing in fascination at the poisonous world-serpent, representing thus man’s psychological attraction to the realm of his bondage in unending birth, suffering, and death.

The god’s head, meanwhile, is poised, serene and still, in the midst of all the movement of creation and destruction represented in the rhythm of the rocking arms and slowly stamping right heel. His right earring is a man’s, his left a woman’s; for he includes and transcends opposites. His streaming hair is that of a yogi, flying now however in a dance of life. Among its strands is tucked a skull, but also a crescent moon; a datura flower, from the plant of which an intoxicant is distilled; and finally, a tiny image of the goddess Ganges—for it is Shiva, we are told, who receives on his head a first impact of that heavenly stream as it falls to earth from on high.

From the mouths of a double headed mythological water monster called a makara the flaming aureole issues by which the dancer is enclosed; and the posture of his head, arms, and lifted leg within this frame suggests the sign of the syllable OM. (359)

Now, let us look at Shiva’s relationship to “ignorance.” Shiva juxtaposed against “binding Ignorance” becomes “liberating Knowledge,” but notice that Shiva does not attack Ignorance, but rather appears to have spontaneously arisen from behind it—literally standing on its back but paying no attention to him. The relationship between Ignorance and Knowledge is like the relationship between the conscious and unconscious meaning of speech as it is understood in psychoanalysis. The structure of that relationship is paralleled here with the relationship of Shiva and Ignorance. Ideally in classical psychoanalysis the former meaning simply collapses under the weight of the latter once the subject becomes aware of the larger whole. The conscious, ignorant ego—ignorance and ego are synonymous in Indian thought—serves as the doorway to and the ground of, unconscious but total knowledge. Once the unconscious whole becomes present in awareness the Ignorance collapses to a single point on the flaming circumference of that Knowledge. But what are the contents or the methodologies of that Knowledge? What kind of human experience is being artistically expressed with Shiva Nataraja? Is it a real experience, or only mythological or at best psychological? Let’s turn to phenomenology, which provides the link from psychology to anthropology.

To address these questions we must again trace Shiva’s history, this time from a different angle, in order to see where Shaivism falls between our experiential and mythological dichotomy. Here I am defining “mythological” as a religion that is held together by a set of adhered to propositions only; in other words, belief or faith in a narrative is all that is needed to “prove” the veracity of the truth claims imbedded in those propositions. On the other hand, “experiental” religion is one that is accompanied by some physiological change in its members as an indication of some phenomenological alteration of experience. (For details of such interactions see neurologist James H. Austin’s Zen and the Brain: Toward an Understanding of Meditation and Consciousness, published at MIT, 1999.) Both distinctions can be found in most religions, so it is more a matter of degrees than of rigid forms. Nevertheless this distinction is important because all religions have their artistic or esthetic repercussions, but at the extreme ends of our dichotomy the subjective affect of a particular religiosity becomes palpably dissimilar—being a Jew feels different than being an Aztec. Indeed, it would be wonderful to explore the differences between Aztec and Jewish art but unfortunately the scope of this paper demands that I stay focused on our Nataraja.

Does our statue teach us something of what if feels like to be a Shiva devotee? Remember that yogic images can be traced back to the Indus Valley Civilization through stone seal impressions as old as 2500 BCE, and that of all the gods Shiva is the greatest yogi (Stokstad 69). The connection with our experiential versus mythological discussion above is already becoming evident on two fronts. First, the experiences of yoga, like that of meditation, are essentially non-narrative in structure. Hence, yogic understanding can’t by definition be essentially mythic in content, because a non-narrative structure precludes having narrative content. The mythic narratives about, and descriptions of, yoga flow and revolve around experiences that are essentially alien to language or linguistic modes of thinking and communicating.

Secondly, the ancient roots of Shaivism (as shown by the stone seals) are firmly planted in an even more archaic soil than yoga, namely shamanism. While writing for the Smithsonian, Geoffrey Samuel, a quantum physicist turned anthropologist, and an expert on Australian Aborigines and Tibetan Buddhism, gave this definition of shamanism: “. . . the regulation and transformation of human life and society through the use (or purported use) of alternate states of consciousness by means of which specialist practitioners are held to communicate with a mode of reality alternative to, and more fundamental than, the world of everyday experience” (8). For a discussion on the “. . . structural differences that distinguishes classic yoga from shamanism,” see chapter eleven of Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy by Mircea Eliade (417). Here our purpose is simply to begin addressing the implications of “alternate states of consciousness” as they pertain to our image of Shiva.

That Nataraja is a view of reality from a different state of consciousness is evidenced not the only by the single large Datura flower over his left shoulder, but also by the smaller, “Garlands of Datura blossoms [that] are woven among the locks of his whirling hair” (Schultes 10). Finding a connection between entheogens and Hinduism is not novel. “Soma [the Amanita muscaria mushroom (Smith 55)] occupied a unique position. Indra with his thunderbolt was more commanding, and Agni evoked the awe that fire so readily inspired…But Soma was special, partly (we may assume) because one could become Soma through ingestion…” (Smith 48). This is doubly interesting because Indra of the Vedas, who had a very close connection with Soma, was replaced by Shiva in Hinduism later texts. Indra’s thunderbolt became Shiva’s “linga of Light.” I will address this “linga” later on. However, it is not A. muscaria that is associated with Shiva Nataraja but Datura. Why?

To answer this question we must try and understand the kind of “altered state of consciousness” that Datura involves. For this I went to the internet and found a description of a westerner who experimented on himself with this plant. The results were illuminating:

The interesting thing about Datura is the power of the experience…Datura is very earthy and familiar. Nonetheless…both [Datura and Ketamine] can be used as tools to explore reality. It’s difficult to explain the difference in a few words. So, I’ll give an example of a typical Datura trip… I’m propped up in bed, reading an amazing book. The topic is really fascinating and resonates with my interests. When I get to the bottom of the right hand page, I try to slide my hand behind the page, to turn it over and continue reading. But there are no more pages, and I flip fresh air. In fact there is no book. I’m propped up in bed, with my empty hands, palms up, lying on my lap. I’m surprised and irritated that there is no more pages. But, the topic was so interesting that I decide it’s worth reading again. When I start reading at the top of the left hand page, the book is about a totally different topic. Which is just as fascinating, so I quickly read to the bottom of the right hand page, and try to flip over the page to continue the story. But, there are no more pages. So I start reading from the beginning again. And, wow, another totally different yet fascinating topic. I read eagerly and come across an amazing sentence. I decide to read it again. My eyes scan to the beginning of the sentence and I start reading. But the topic has changed again. And so it goes. Basically, any hesitation on my part, any break in the flow, would switch the topic. Always great reading though. So I languished in bed for a few hours reading my endlessly fascinating, Infinity Book.

One can see why this plant would become associated with the creator and destroyer of worlds. Even though, we can only imagine how such a plant would affect the mind of an ascetic trained in meditation and yoga, the phenomenology of this kind of altered consciousness seems appropriate for the ontological philosophy of the Shaivite. This in turn begs the question of the ontological status of these created and destroyed worlds.

To be fair we must acknowledge that Shaivism’s ontology is more about the energy or Shakti that creates “worlds” than it is a description of the “worlds” themselves. The energy in these “energy ontologies” of Shaivism is equated with consciousness and consciousness is related in some way with its contents. But how are the contents of consciousness related to the energy that is Shiva’s Shakti? And, if “manifestation” has to do with Shakti, what is Shiva? And can we learn anything from gazing upon our statue? I will address these questions in reverse order, which is from the easiest to the most difficult.

Yes, much is explained in the figure of dancing Shiva. His dance is one of pulsation and heat, of rhythm and motion, but also of tranquility and stillness, of release and freedom. His calm unperturbed face shows that he is unaffected by the energy of his whirling body. The energy seems to flow through him more than it seems like it is him. As a symbol of personal non-dualism he is both all and nothing. As a symbol of manifestation and destruction he is both the ignorance upon which he stands and its annihilation. Like the “Infinite Book” that comes into existence at the calling of the reader’s attention, the ego comes into existence at Shiva’s beckoning. Maybe like the A. muscaria and Soma, one becomes Shiva “through ingestion.”

But what is Shiva? Shiva as Lord of the Cosmic Dance is Shiva embraced by Shakti. He is space in motion. He is mass aware of its energy. He is the intentionality of subjectively created objects.

And how is this kind of relationship possible? Energy is correlated with consciousness which in turn is interrelated with the objects of experience by the sheer structure of the universe itself. But we don’t have to take the beliefs of either the religious fanatics or drug fiends at face value. We can turn to our culture’s own experts on the nature of the physical universe instead. Surprisingly what we sometimes find is yet another description of Shiva’s dance:

The exploration of the subatomic world in the twentieth century has revealed the intrinsically dynamic nature of matter. It has shown that the constituents of atoms, the subatomic particles, are dynamic patterns which do not exist as isolated entities, but as integral parts of an inseparable network of interactions. These interactions involve a ceaseless flow of energy manifesting itself as the exchange of particles; a dynamic interplay in which particles are created and destroyed without end in a continual variation of energy patterns. The particle interactions give rise to the stable structures which build up the material world, which again do not remain static, but oscillate in rhythmic movements. The whole universe is thus engaged in endless motion and activity; in a continual cosmic dance of energy. (Capra 225)

The details of this subatomic dance are as interesting as anything I’ve mentioned so far and I regret that they too are out of reach. I will have to pass over them and make only a few general observations apropos the physical reality. First, if “physical” means “matter,” then there is no physical universe. At least not since Einstein, that famous mahascientist, showed us that mass is just another way of saying energy traveling at the speed of light squared. (Does this mean that supernatural light has a mathematical relationship to the brightest natural light?) Also, much has been written about how “observation” can change the course of a traveling subatomic particle. Indeed, under some observational condition a particle of light is not a particle at all, but a wave like the sound waves of the syllable OM. I even saw one book years ago that equated Superstrings with axis mundi experiences like that of Shiva’s “linga of light” or Indra’s thunderbolt. I like this image of the real being wrapped up along cosmic strings like our biology is wrapped inside the DNA molecule and I also like its equation with Shiva lingas. It would mean that the different layers of reality are connected through a kind of parallel structure. Could it be that the ignorant ego upon which Shiva stands is at that moment experiencing that leg as a thunderbolt or linga? Note that: “…linga Shiva is not one god among others, but the unfathomable One. In this ‘partless’ form, Shiva transcends even Shiva himself… This is not Shiva, beautiful or ugly, dressed in silks or tiger skins, wearing the crescent moon or the necklace of skulls. This light is the mysterium tremendum which finally cannot be described or comprehended by any or all faces and attributes” (Eck 109). But regardless of what might or might not adhere to these invisible cosmic lines that transect the various layers of existence we must address one last anthropological and scientific question, one that will lead up into our promised philosophical discussion.

What is the ontological status of either the “Infinite Book” or of the “stable structures which build up the material world” as a result of particles dancing in and out of existence; are they real; are they less real or more real than what I’m experiencing right now? What is the ontological status of Shiva Nataraja, or the content of that work of art? How could we know? The answer is that we cannot know uniformly across wildly divergent experiences such as “state of mind.” Right now there are no invisible books real to me. But if one were to mysteriously pop into my hands for whatever reason it would most likely be as real as the lack of such a book is now. Also, the fact that the lack of a book is more often the case proves nothing, because the “reality” of no book is the same as that of yes book. So how would we study reality?

Here we can turn to philosophy for both a warning and a clue. The warning comes to us as axioms entreating us to withdraw from ethnocentric, Eurocentric, phallocentric, and logocentric ways of thinking about such problems. Abandoning all of these conceptual traps will be hard but promising. Take, for example, the problem of avoiding logocentrism: “Without logos, many contrasts cannot be made to function as principles of the sort of theory philosophy has sought. Thus the contrasts between metaphorical and literal, rhetoric and logic, and other central notions of philosophy are shown not to have the foundation that their use presupposes” (Audi et al. 181). It sounds difficult, but one can see how this deconstructive approach to theory might just someday help us in our understanding of the paradoxical worlds of quantum physics, shamanism, and yoga.

The philosophical clue comes from William James who after exploring altered states of consciousness had this to say:

One conclusion that was forced upon my mind at that time, and my impression of its truth has ever since remained unshaken. It is that our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different. We may go through life without suspecting their existence; but apply the requisite stimulus, and at a touch they are there in all their completeness, definite types of mentality which probably somewhere have their field of application and adaptation. No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded.[my emphasis] How to regard them is the question—for they are so discontinuous with ordinary consciousness. Yet they may determine attitudes though they cannot furnish formulas, and open a region though they fail to give a map. At any rate, they forbid a premature closing of our accounts with reality. Looking back on my own experiences, they all converge toward a kind of insight to which I cannot help ascribing some metaphysical significance (qtd. in Smith 26).

At some point our culture will have to address this other “centrism”; the centrism of everyday consciousness. Our everyday consciousness, like language, did not evolve to address these kinds of problems. If we want answers, or at least better questions, about the nature of reality it might behoove us to take James’s advice.

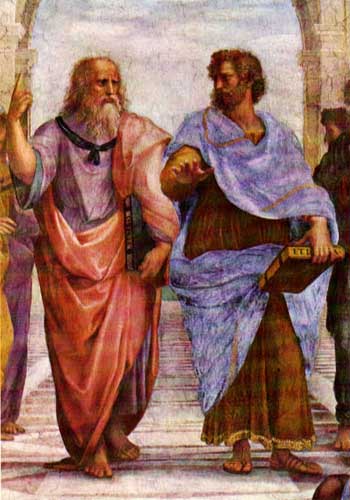

And now, having come to the end, having dragged this religious icon through the mental landscapes of history, psychology, anthropology, as well as physics and philosophy, we are finally ready to give one last shot guessing what this images means. I’ve looked as closely as I can, given my poor vision, at the subject matter of Shiva Nataraja. All that is left is to give one final summation of its content. And for that I must ask you to take one last look at our perfected late Chola period bronze statue of Shiva. Notice that the perfect golden (bronze) circle is all aflame. Indeed, it is as if the craftsmen of the late thirteenth century wanted literally to create an image of the Sun. Here, Shiva, the “Lord of Caves,” has become the Sun: the Sun outside Plato’s Cave, the Sun that Dante saw when Beatrice lifted him off of the spiraling mountain of purgatory. All that is left is to address, what is Shiva? What is this Sun that has risen again and again through the page of literature? To respond to this question it seems appropriate to enlist the words of Allama Prabhu, a tenth century South Indian poet for help:

Looking for your light,

I went out:

It was like the sudden dawn

of a million million suns,

a ganglion of lightnings

for my wonder.

O Lord of Caves,

If you are light,

There can be no metaphor. (qtd. in Ramanujan 168)

Works Cited

Audi, Robert, et al. The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. New York: Cambridge UP, 1995.

Austin, James H. Zen and the Brain: Toward an Understanding of Meditation and Consciousness. New York: MIT UP, 1999.

Capra, Fritjof. The Tao of Physics. Boston: Shambhala, 2000.

Campbell, Joseph. The Mythic Image. New Jersey: Princeton UP, 1990.

Datura Trip. 14 June 2000. Erowid Experience Vaults. 5 June 2003 Eck, Diana L. Banaras: City of Light. New York: Columbia UP, 1999.

Eliade, Mircea. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. New Jersey: Princeton UP, 1974.

Feuerstein, Georg. The Shambhala Encyclopedia of Yoga. Boston: Shambhala, 1997.

Goetz, Hermann. The Art of India. New York: Greystone, 1964.

Harle, F.C. The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. London: Penguin, 1987.

Hopkins, Thomas J. The Hindu Religious Tradition. Belmont: Wadsworth, 1971.

Ramanujan A.K. Speaking of Siva. Baltimore: Penguin, 1973.

Samuael, Geoffrey. Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies. Washington: Smithsonian, 1993.

Schultes, Richard Evans, and Albert Hofmann. Plants of the Gods. New York: Alfred van der Marck Editions, 1979.

Smith, Huston. Cleansing the Doors of Perception: The Religious Significance of Entheogenic Plants and Chemicals. New York: Putman, 2000.

Stokstad, Marilyn. Art: A Brief History. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment