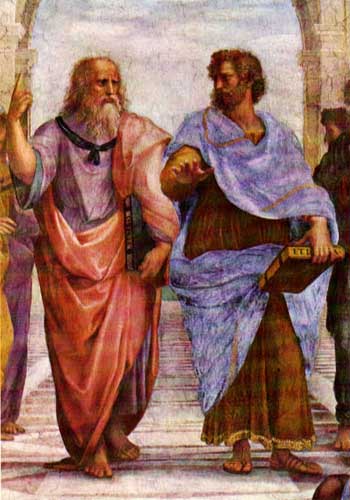

“We must concede that the Ideal Theory, in the precise form in which it was taught in the Academy, was not given to the public in writing.” --Fredrick Copleston, S.J.

Plato to Socrates, Welfare.

Do you remember the speech that Diotima gave you on love, the one that you recited at the drinking party in honor of the tragedian Agathon’s first triumphant production? Alcibiades and Aristophanes were there, as was Phaedrus who memorizes all your speeches! And lucky for me that he does because last week he recited your speech to me while we reclined under a chaste-tree; tall and very broad, high as it is wonderfully shady, the tree was in full bloom and the whole place was filled with an intoxicating fragrance. From under the plane tree the loveliest spring runs with very cool water—our feet can testify to that. The place appears to be dedicated to Achelous and some of the Nymphs, if we judged correctly from the statues and votive offerings. I say that it is a beautiful place, and one that Phaedrus loved dearly.[1] I would suggest that you, Socrates, take the young Phaedrus there some afternoon—you know he loves you dearly—but alas the river runs outside the city walls, and so I fear that you will not venture outside just on my suggestion.

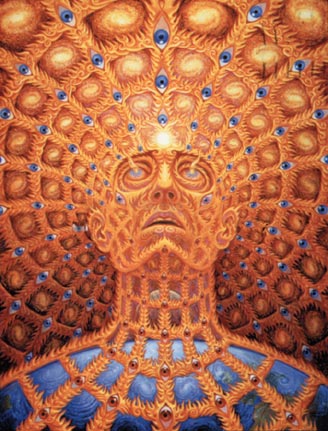

I tell you this not because I was there last week, but because I returned there yesterday. A day that will forever be engraved on my soul, Socrates, because it was the day that I discovered for myself what it means to be Beautiful. Indeed, I will tell you exactly how it came about that I happened with my own mortal vision to see the immortal forms themselves. They were just as you said, Socrates: pure and unchanging, simple eternal reason! Thanks to Diotima, Achelous and the lovely nymphs, for it was through their influence that the walls of this ignorant world came to recede away from my Soul—revealing the Beautiful Light beyond.

All week long I thought about what you told Agathon and his friends; no one has talked about anything else. I’m sorry I missed the party, but Meno is right when he says you practice a kind of sorcery. Indeed, your spells are so strong that you continue to bewitch me through those whom you’ve bewitched. Really, Socrates, after a week of thinking continuously about beauty I came to rest under this enchanted tree yesterday to continue my pondering.

Then I went over your speech and in my mind I could hear you saying, “…there surely are those who are even more pregnant in soul.” And indeed this is how your words made me feel, Socrates: like I was about to give birth. The nymphs slipped my bare feet back into that ever-splendid stream, while still my thoughts kept revolving around your words. You said, “Even you…could probably come to be initiated into these rites of love.” And Socrates, I said to myself, “Yes! I want to be a poet and a statesman because there is nothing I desire more than what is beautiful and what is just.” (How different things are today!)

I believe, Socrates, that it was at that very moment when my soul was kindled, and that it was my pure desire for what is true, beautiful, and good that was the initial spark. Your words were still in my head, yet somehow they seemed to have expanded, like a sponge in water, and with their expansion the perimeters of my mind seemed to grow apace.

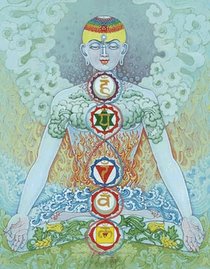

Your spell carried these words, “A lover who goes about this matter correctly must begin in his youth to devote himself to beautiful bodies. First, if the leader leads aright, he should love one body and beget beautiful ideas there; then he should realize that the beauty of any one body is brother to the beauty of any other and that if he is to pursue beauty of form he’d be very foolish not to think that the beauty of all bodies is one and the same. When he grasps this, he must become a lover of all beautiful bodies, and he must think that this wild gaping after just one body is a small thing and despise it. After this he must think that the beauty of people’s souls is more valuable than the beauty of their bodies, so that if someone is decent in his soul, even though he is scarcely blooming in his body, our lover must be content to love and care for him and to seek to give birth to such ideas as will make young men better. The result is that our lover will be forced to gaze at the beauty of activities and laws and to see that all this is akin to itself, with the result that he will think that the beauty of bodies is a thing of no importance. After customs he must move on to various kinds of knowledge. The result is that he will see the beauty of knowledge and be looking mainly not at beauty in the single example…but the lover is turned to the great sea of beauty, and gazing upon this, he gives birth to many gloriously beautiful ideas and theories, in unstinting love of wisdom, until, having grown and been strengthened there, he catches sight of such knowledge, and it is the knowledge of such beauty…”

The effect of those words on my soul, Socrates, I would have described as like the effect of light shinning down into a well, but now after seeing what I saw under that tree I know not to use such words as “light” so unconscientiously. Still, your words were like the blue print for a magic ladder that my soul later constructed out of desire for what is good, virtuous, and just. It, as you know, was a ladder whose lowest rung was at the very center and contained only itself, but whose highest rung contained all others nestled one inside the other, like an egg containing an egg and so on, all the way down. Also, the lowest rung is constantly changing and in great flux, and therefore it is the hardest to grab and to hold firm, or to crack open; but from the topmost rung, one sees that it—the highest realm of being—is all there is, all there ever was, and all there ever will be. Socrates, it is a mystery, but one that you clearly reveal to those who have ears to hear: “So when someone rises by these stages, through loving bodies correctly, and begins to see this beauty, he has almost grasped his goal. This is what it is to go aright, or be lead by another, into the mystery of Love: one goes always upwards for the sake of this Beauty, starting out from beautiful things and using them like rising stairs: from one body to two and from two to all beautiful bodies, then from beautiful bodies to beautiful customs, and from customs to learning beautiful things, and from these lessons he arrives in the end at this lesson, which is learning of this very Beauty, so that in the end he comes to know just what it is to be beautiful.”

Let me not waste your time repeating to you your own words. Socrates, I want only to hold up the knowledge that your beautiful soul has delivered. The seeds came from Diotima, and you gave them to Phaedrus who then planted them in my heart so that Achelous might water them. And this, dear friend, is what grew:

The water flowing up into my soul from the stream must have made your words swell, because shortly after repeating to myself, “…so that in the end he comes to know just what it is to be beautiful,” I could no longer recognize my own mind because it was full and in fact overflowing with the meaning of your words. I was amazed at your power, and I thought to myself that the Oracle was right about you being the wisest man in Athens, and then I remembered what the Oracle tells everyone: Know Thy Self.

So, naturally I began, introspecting, questioning myself, but the water mixed with your words had a strange intoxicating affect on my thoughts. I thought of myself and instantly I saw myself “in” the water—but nothing else. It was me, clear and crisp in every detail; I was an attractive young body, so I looked deep into my eyes for what was beautiful but saw, unlike Narcissus, only the opaqueness of the dark Earth. So, then I widened my gaze and to my amazement I saw myself multiplied. I must have seen a dozen me’s, each different from the other. The son of my father was there, as well as husband of my wife. Your most loyal student was there, as was the student of poetry and politics. We—by which I mean every possible me—were all there, suspended in the water before my mind’s eye; that is the mind’s eye of each and every one of us!

But, Socrates, this was only the beginning. It was only the first and lowest rung in the ladder, because just then all the different me’s came together again. We all overlapped each other in every possible way imaginable, and some ways that are simply unimaginable; and at the end of that process, stood I as I had never seen myself before! For the first time in my existence I was simple and solid, full and complete, pure and beautiful. In other words I was whole. I could see through all the various me’s to the eternal form of myself. I became aware of my Soul.

Then I stepped onto the second rung, because at that moment when I was myself whole and eternal I became surrounded by everyone in my family. However, this time I saw everyone just like I saw myself—whole. Each one of them, my mother, my father, my step father, and my brothers were all there, as wholes. And through each one of them—through each whole of them—I could see all their changing and particular selves. The soul of each embraced its own multiple personalities; that is, Socrates, many qualities came to overlap and create the many particulars that made my mother. For example, all the qualities of her particular childhood were alloyed together in such a way as to impress on my knowledge her very Childness. And in the same way her Motherness, her Wifeness, her Womanness, and many other wholes were recollected by my soul’s climbing. Each one of her forms was beautiful, and it was my love of the beauty that I saw that brought me to them, and brought them together in me; and once all my mothers were together—in truth they had always been together—that Whole of the Wholes, that unity of particulars that is my mother was the most beautiful Mother of all.

But this, Socrates, is just to give an account of one member of my family. In truth, every member of my family stood before me, and it was the first time in my life that I’ve seen any of them as clear translucent wholes; I felt like I was looking right through their souls to the forms that are each one of them. And although this was still early on, now it was not as if I had my feet in the enchanted stream, but as if my whole self was submerged in those sacred waters, and all that I saw and knew was nothing but that water flowing through me.

For at that moment, each one of the members of my family—now as wholes—were like currents in a mighty stream flowing together; indeed Socrates, the very next moment brought all those currents together into one fathomless whirlpool that was my family as a whole! The form of my family was there standing before me, flowing through me, and extending from the very foundation of our human traditions upwards all the way into the heavens.

And then, Socrates, I realized one step later that one can both see and see through the forms. Indeed, like with all the forms, looking into the Whole that was my Family was like looking into a window that separates us from a tremendous beauty just beyond ourselves. Still, this Whole that was my Family was in the form of Apollo; I saw how the love of each member of my family for Apollo brought each and every one of them into a relationship with each other that was the form of that mighty God. It was as if the stamp or the imprint of radiant Apollo was, even across the generations, holding my family firmly together as a Whole.

Socrates, the gods are so great! Because, just then as I was seeing for the first time in my existence my family as a Whole—I took another step—and all the families of Greece stood out from behind my own, and like mine each and every one of them were Wholes in the shape of a God. Yours too was there, and like mine it was impressed with the form of Apollo; indeed, all the gods were there as Wholes. Phaedrus’s Family was there in the form of Hermes, and Aristophanes’ in the form of Dionysius. In truth, all our Gods were there in the form of our Greek families.

I tell it to you like this, Socrates, because the feeling was that I was still only seeing the beginning of Wisdom and not its end. Unfathomably, the gods were not only forming all the families that worshiped them but they were also formed by them. But in truth Socrates, I could see that the gods had always been and that they would always be. What I saw, I once would have said was brilliant like a giant bonfire made from the thousands of beautiful torches that are our Greek families. But I was still in the Water and had not yet see Air, let alone the real Fire.

What I’m groping hopelessly to write down for you, Socrates, is that I saw for the first time in my existence the totality of our Greek culture as a whole—a whole whose contours are the eternal love relationship between ourselves, our families, and our gods. But, Socrates, I swear on vengeance from Apollo that our Greek Whole was one from among many. In fact, the streams, made of their currents—the families made of their members—had merged not only into might rivers—the Gods—but into a whole tributary system—the form Greekness itself!

And still, at this step, this whole cultural system of ours was only one among many because looking down from what is beautiful within our Whole culture I could see, as if looking down from The Beautiful itself, many such beautiful cultures. The Hebraic, the Egyptian, the Indian, they were all there inside me, Socrates, inside what is eternal and beautiful and good in me. I saw them all; I saw not only the differences but the unity too. And what’s more, Socrates, I could see not only the different river systems but also the mountain ranges that separated them. Up until now I had really encountered only Water, but now I was discovering Earth. Indeed, I realized that up until now I had my entire life taken Water to be Earth. That is how ignorant I was, Socrates!

Oh, Sweet Socrates, take a deep breath and ponder what I tell you here. The form of those eternal mountains was no other than the form of Nature, of Things, of physical-objectsness—of material existence itself! It was here that the ladder began to fade away from under me and it was also here that I noticed that the mountains were outside the waterways, like our material existence is outside our cultural existence, yet it was only from inside the form of things—seen as a whole—that I could see the beautiful outside of that form. Indeed, it was more beautiful than anything I had yet seen, so beautiful in fact that I realized that what I had taken for being outside the forms of culture was really the form of Culture itself—and that final form, that form of forms, Socrates, is really the World—with itself and with everything in itself too.

And it was this, this Being-Eternal, this form of everything that is beautiful and true and good, this form of the Good itself, Socrates, that I came to realize through the logic of your reason. So, I stop here to thank you for saying only what is always true and beautiful and good, because it was your speech that put me to climbing the steps for myself.

Still, this is only the middle of my story, because in seeing the form of the Good with my mind’s eye I came to see—I should say “be”—a third level of Being, because what happened there at the level of the Good was that all my questions were answered; and when the answers came all my desires were emptied of their wants, and I myself became clear of desire, and of want, and of need. I died that moment, Socrates, but my vision, my soul, carried on without me—for in that eternal moment of the Good the opposites came together and turned themselves inside out, leaving only the soul—as a loving manifold that trans-forms—to further unfurl.

Everything I’ve written, from the moment I put my feet in the water till now, is really beyond words, but from now on what I write is beyond even one’s personal imagination, because beyond the Good my Soul was the World and it was the Soul of the World, it was of all and it was One. I was the Air and like the air I knew all things because I embraced all things, both from the inside and the outside: there was no Earth and no Water but only Air. Air was the only reality. But this Air that I was, this World-Soul, began to be flooded with a kind of gratefulness, a kind of thankfulness; I was a kind of burning love, which was kindled by the void, caused by the evaporation of desires, wants, and needs, caused by the answering of all questions. And it was there, after I had seen all, known all, and become all, that I came back to my senses.

Yes, Socrates, it was only then that I came to my senses again. I saw my feet in the water. I looked at my hands. I looked at the ground around me and at the sky above me. Everything was exactly as everything had always been, but I had changed. Really, the only thing that was different was me; my body was there, and my mind was there too. I remember thinking, “Incredible, everything is so clear.” It was as if the water that swelled my thoughts had finally receded and in doing so it had also washed away all my assumptions and preconceptions, leaving everything exactly as it really is and not as it had appeared my entire life previously. The tree, like everything else, was there but now it commanded a level of bare authentic reality that I had never seen. The tree was the tree, nothing more and nothing less. It was there in the world along with everything else. Yet strangely, it and the World that contained it felt like they were inside me. And I…I was everything and I was nothing: I was not present to my own self. I was not aware of my separate self. There was no Plato; there was only the world’s Soul. And through it all things were seen and known eternally, but now in the most matter-of-fact ways: the tree, the grass, the water—my hands—all was simply such as they really are. But also, I mean that they were such as they really are to perception only, and not to the Perceiver. I say this, Socrates, because although up till that moment I had repeatedly encountered higher and higher levels of being, of reality, I was still to know one more. Being-itself.

At this point, it was as if I had crawled out of my self as if I had crawled out of a cave and into the wide open landscape. For the first time of my existence I really saw the land and the sky. I was free from all desire, and as a consequence everything appeared perfect and beautiful exactly as they were. Everything was eternal and belonged to the world’s Soul.

In truth, Socrates, all that was left of Plato was devotion and gratitude and love. I fell in love with everything equally, and wanted to pray. And I did pray; spontaneously, uncontrollably, I prayed, to the All, in appreciation for Everything. And, for the first time in my existence every layer of my being said, “I love and thank You.”

Indeed, Socrates, the love that was now the world’s Soul—the love for the real—became so hot and radiant that I, as if in search of the source, looked up at the sun and…Blazes! All was alight! All was ignited into Fire and Sun, and Light—a Light that was nothing but always Awareness, nothing but always Being, and nothing but always Joy—and I was that Truth, that Goodness, that Beautiful Eternal-Light!

I don’t know how long it took me to crawl out of my cave, or how long I sat there breathing in the landscape before looking upwards. And I don’t know how long I spent with the Sun, because from the moment I took your speech on Beauty seriously I was outside time.

Socrates, I write to you only to thank you. I know that I’m not telling you anything you haven’t yourself told us in private. I understand now why you refuse to write anything of importance down on paper, and why you wish for us to do the same.

Finally, I know now that I must give up poetry and politics. I wish only to write philosophy. But don’t worry because I promise not to give away your secrets. Besides, it does not help anyone to be told the truth, for each must find his own way. Actually, I want to write about this experience, and I feel as if I could spend my whole life doing so. But I will write it down only in such a way as to help others to find and climb the ladder. It will be an invitation to question and to ponder. Who knows, Socrates, maybe I could actually be of some influence. Either way, what in this world of appearances could be more beautiful than to love the beauty of the science of the Beautiful?

[1] I’m quoting the description directly from Plato’s Phaedrus, to imply that the location was a “real” one known to Plato and Socrates.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment