Religious experiences and especially mystical experience are rare, but nevertheless given the impact they have on individuals, communities, and traditions they are important enough to give serious attention to. In particular, the ineffable nature of mystical experiences is important to note because ineffability in effect ensures that the various religious narratives that results from such experience can not be literally true and therefore can not be literally in contradiction with each other. In short, religious narratives that arise from mystical experiences can not logically be mutually exclusive. More importantly, the fact that today’s multicultural social environments are yielding more and more individuals who claim dual religious identities (e.g. Messianic Jews, people who claim to be both Christians and Buddhists, etc) bespeaks of the emergence of multicultural religious and mystic experiences; such experiences might suggest a deeply spiritual way of resolving long entrenched religious conflicts.

The three monotheisms, for example, are like siblings who as adults cannot agree on what life was like at home in their youth. Pluralism suggests that the three children of Abraham—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—need to look together at the nature of their memories, at how those memories form are culturally constructed realities that divide their three religions, and at how their differing constructions are grounded in the same reciprocal processes by which the Real comes to be symbolically coded, and by which those codes lead one to the experience of the Real.

I take it as axiomatic that these two related processes create a feedback loop between upon which religious communities and tradition are founded. That is, religious narratives and symbols are claimed by their adherent to have arisen ultimately from religious experience and promise to guild true believers back to that ultimate experience from which these narratives came.

However, a multicultural reconstruction of those religious narratives and symbols has likewise begun to arise from the multicultural religious experiences within pluralistic societies and they too promise to lead others to a now multicultural religious experience that can yield a deep sense of unity that cuts across previous exclusivist claims to religious truth. Although many people resist anything that looks like “cultural relativism,” such multicultural religious experience can expands the experiencer’s self-identity to include what would otherwise constitute “otherness” in a way that ameliorates those fears Moreover, the identity that is constructed from multicultural religious experience—because of the greater sense of unity in difference—can make us immune to those forces that would have us fight over any particular set of narratives or symbols.

Still, a critic might claim that pluralism not positive and that it is just creates another set of beliefs competing for adherents along side those of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Indeed, according to the Harvard sociologist Randall Collins, there are two ways of understanding what it means that there exists multiple and contradictory description of reality. The first is to suspect that, “…multiple realities and competing truths will turn out to be complementary….We may hope that the competing factions of philosophers or sociologists are pursuing multiple paths of advance into the same wilderness. But [a second view] is also possible… [namely that] the paths may never intersect….that the future will consist in still further fanning out rather than convergence” (Collins 879). However if the critic is patient, I believe that from the work of Paul Tillich and John Hick, I can show that religious pluralists are justified in speaking as if the former possibility is indeed the case, while actually recognizing that neither possibility can be literally true—due to the ineffable nature the Real as revealed even in mystic experiences generally.

To begin with, both Hick and Tillich focus on the nature of symbols in relation to Reality, a relationship that Kantians might call one of mediation between phenomena and noumena. It is also understood that the particular symbols of each of the Abrahamic traditions function by the same means and to the same ends; each is a tradition that tries to lead one—semantics aside—from ideas of god to God him/her/its self. No particular culture can hold in its solitary possession the keys to what Hick calls, “our final salvation/liberation/enlightenment/fulfillment” (Hick 566). Because, in his words:

Each of the great religious traditions affirms that in addition to the social and natural world of our ordinary human experience there is a limitlessly greater and higher Reality beyond or within us, in relation to which or to whom is our highest good. The ultimately real and the ultimately valuable are One, to give oneself freely and totally to this one is our final salvation/ liberation/ enlightenment/ fulfillment. Further, each tradition is conscious that the divine Reality exceeds the reach of our earthly speech and thought. It cannot be encompassed in human concepts. (Hick 566)

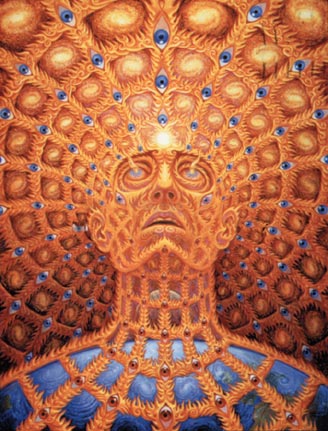

All religious architectures have as their cornerstone the ineffable experience of the Real. Such experience, however, when “brought back” into the phenomenal world and redressed in either rhyme or reason has historically lead to exlusionist claims, because—prior to the multiculturalism of pluralistic societies—religious experience tended to be the result of single set of religious claims and thus tended to reinforce that particular set of symbols, narratives, practices, etc.

However, this exclusionist consequence is not inevitable; for example, notice how Paul Tillich describes the mediating role that symbols play in our journey to the transcendent. He explains that, “…everything in reality can impress itself as a symbol for the special relationship of the human mind to its own ultimate ground of meaning…. [That is] religious symbols are taken from the infinity of material which the experienced reality gives us” (381). The idea here is that there is a sense in which symbols play an absolutely crucial role in religious experience, but also there is a sense in which they are absolutely arbitrary. In other words, despite their seeming ungroundedness they do play a necessary role in guiding us to what John Hick called the Real.

In fact, it is because reality is surprisingly and exquisitely manifold—yielding various scientific, social, and metaphysical descriptions—that more often than not our first clear sight of one of its folds is enough to blind us to its further unfolding. Therefore a pluralistic study of religious phenomena can not only help us keep our hearts and minds open, but it can also enlarge the categories through with we experience the religious.

In the case conflicting views of Jews, Christians, and Muslims it is doubly important to recognize that often, just as in the past, what on sees is what one is culturally conditioned to see; however, unlike in the past, in today’s multicultural societies people, say, someone undergoing a religious experience who is equally familiar with Catholic and Muslim views can emerge from that experience with an acceptance of both the symbols of the trinity and the language of Allah. Messianci Jewish community which arose in the 1960’s is another example.

Moreover, that person may begin to speak pluralistically about his or her experience and thus contribute to others attaining multicultural religious experiences. In other words I agree with Hick when he writes that:

…even the most advanced form of mystical experience, as an experience undergone by an embodied consciousness whose mind/body has been conditioned by a particular religious tradition, must be affected by the conceptual framework and spiritual training provided by that tradition, and accordingly takes these different forms. (570)

But I would also go further and say that it must also be understood that if the tradition in question is itself multicultural and pluralist, then what results from mystical experience is a reaffirmation of a deep unity that transcends previous mono-cultural descriptions of reality.

Randall Collins also makes clear the crucial point about the relationship between symbols and reality, or the “images or concepts that have been generated at the interface between the Real and the Different patterns of human consciousness” (Randall 347). Again, one needs to take only a small step further to see its pluralist implication. For example, in The Sociology of Philosophies, he makes this observation:

Symbols are the residue and the continuity of experiences over time (my emphasis). They flow through individual brains, shaping their attention and emotions, setting up the possibility of transcendent private experience, and then bringing those experiences back into the network of social relations which give them meaning, and which re-create the possibility of other person’s acquiring their own private experience… Social reality is at once creating and bringing down religious experience. (my emphasis) (Randall 347)

That being the case, it seems clear that rich multi-cultural societies operating through rich multi-symbolic systems are the perfect context in which to give rise to rich multi-cultural religious experiences. And, given the increasingly pluralistic social reality of today, it should be obvious that religious pluralism—though still immature—is the only viable option in the long run for this multi-cultural, and increasingly integrating, planet; that is, if the planet is to remain multi-cultural and integrated. Authentic religious pluralism strips pogroms, jihads, and crusades of their ideological impetus. Still, given the cannibalistic nature of some of our planet’s dominant cultures, the continuation of the trajectory of religious pluralism as an antidote to religious conflict is not as predictable as I might have made it sound.

In fact, many people feel that religion itself is the main engine driving today’s greatest conflicts and tend to reject any “religious solution” claiming that such a solution could only lead to cultural relativism—what many fear is the implication of religious pluralism. For that reason, Bikhu Parekh’s discussion of human nature, in Rethinking Multiculturalism, is an important contribution to our understanding of ourselves us cultural creatures. Although he explicitly eschews cultural relativism as a fact that needs to be a part of any account of our species as social beings, ironically, his work effectively demonstrates that cultural relativism is indeed the case.

Parekh’s views on multiculturalism are predicated on precisely the fact that no single individual from any one particular cultural viewpoint can legitimately pass judgment on someone of another culture without first coming to some understanding of the moral and ontological assumptions embedded in that culture. The resulting cross-cultural evaluation, he argues, will then be a reflection of “our” values juxtaposed against “theirs” in a way that the pragmatic concerns for what has been agreed upon as minimal moral values—which are not seen as eternal or culturally independent—are brought to the forefront and used as a standard for mutual evaluation of each other.

Specifically, Parekh describes culture as that which lies between the universal and the particular in human beings. He argues, for example, that is universal, i.e. biology, acquires different meanings that are associated with any particular culture, while, what is particular, i.e. symbols, are grounded in what the universally transcends culture. In other words, what is particular to a culture, like religious narratives, is related to different cultures by virtue of being equally embedded in and limited by what is physically beyond culture, like biology. Moreover, for Parekh the relationship between what is cultural and what is not is a dialectic one. That is, Parekh claims that biology, though universal, is always seen through cultural lens and that therefore we can not tell where one begins or where the other one ends. Indeed, this dialectic, he claims, has created a situation where:

[N]ature has been so deeply shaped by layers of social influences… [that] we cannot easily detach what is natural from what is manmade or social…. [In short] cultures are not superstructures built upon identical and unchanging foundations…but unique human creations…[that in turn] gives rise to different kinds of human beings. (122)

However, I argue there is a problem in Pareck’s philosophy that can best be address by understanding the true implications of cultural relativism, and thus plausibility of pluralistic religious experiences of the Real. That is, there is a danger in believing in “different kinds of human beings,” but a danger which can be made innocuous by accepting the actuality of cultural relativism. The danger is that someone might—as has often happened—come along and argue that some kinds of humans are more important than others, that perhaps some nations have a manifest destiny to dominate others, or that infidels are a threat to one’s true god, or that one’s people are the chosen while others not; that is why the existence of cultural relativism is so important to recognize. In affect, cultural relativism states that if one culture is valuable then all cultures are valuable.

There are real differences between cultures which simply can’t be theorized coherently because the very notion of coherence only has meaning from a consistent set of cultural values. Multiculturalism is itself such a set of liberal cultural values. It cannot yield any meta-view on the inherent worth of culture as such. For that reason, the value of Parekh’s work lies in his attempt to theorize from an academic, and non-religious, perspective on the practical consequences of cultural relativism. But Parekh denies the role that the assumption of cultural relativism plays in his formulation of “pluralist universalism,” and in doing so he misses much of the value of his own work.

Moreover, the fears that secular theorists of pluralism have of being labeled “cultural relativist” need not be shared by their religious counterparts. Because unlike secular multiculturalism, religious pluralism is ultimately founded on a multicultural religious experience of the Real that while ineffable in itself, like all mystical experience, yields the multicultural religious understanding that all non-mystical experiences, cultural and otherwise, are grounded not in the eternal but the temporal, and are thus historically contingent and thus culturally relative. In other words, the Real once experienced and multiculturally understood eliminates the unfounded fears of “relativism” by grounding ones existence in that which transcends time, history, and culture. In this respect, Pareck was only half right when he wrote that, “cultures are not superstructures built upon identical and unchanging foundations.” That is, he does not understand the ineffable nature of those “foundations” he cannot understand that one cannot say either that those foundations are identical or different, unchanging or dynamic. Indeed, it is because the Real is ineffable that phenomenal reality can absorb so many different cultures, or “superstructures.”

Works Cited

Austin, James H. Zen and the Brain. 1998. Cambridge: MIT UP, 2000.

Collins, Randall. The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Cambridge: Belknap-Harvard UP, 1998.

Hick, John. “Religious Pluralism.” Philosophy of Religion: Selected Readings. Eds. Michael Peterson et al. New York: Oxford UP, 2001.

Mackie, J.L. “Critique of the Cosmological Argument.” Philosophy of Religion: Selected Readings. Eds. Michael Peterson et al. New York: Oxford UP, 2001.

Peterson, Michael, et al. Reason & Religious Belief: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion. New York: Oxford UP, 2003. (PETERSON ET AL.)

Peterson, Michael, et al, eds. Philosophy of Religion: Selected Readings. New York: Oxford UP, 2001.

Tillich, Paul. “Religious Language as Symbolic.” Philosophy of Religion: Selected Readings. Eds. Michael Peterson et al. New York: Oxford UP, 2001.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment