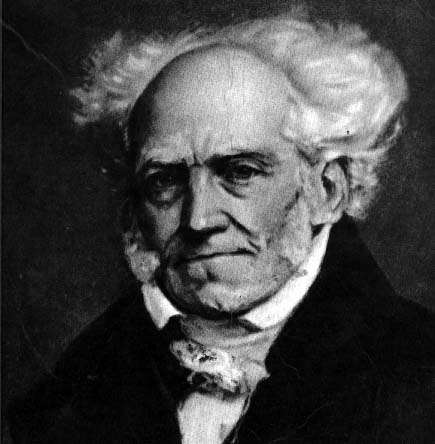

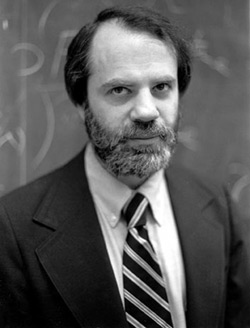

In the 20th Century, both the Analytical and the Continental traditions in philosophy took too sharp a linguistic turn. Rather than progressing forward, they began driving in hermeneutic circles through possible worlds. Common sense demands that we recognize that the meaning of “water” is not H2O or XYZ, depending on which Earth you’re on, nor is everything a text. The current philosophers’ misunderstanding of the nature of language has affected almost every subject touched on by modern thinkers, a fact that is also true of the field of religious studies and Eastern philsophy. A better way of understanding the nature of language, and one that does less violence to the nature of religion, is that of Noam Chomsky. However, this paper is less about language than it is about religion, so an explication of Chomsky’s compatibility with Eastern philosophy will regrettably have to wait for a future opportunity. Nevertheless, we can begin to lay the framework for future theoretical construction. Quite apart from his brilliant work on language, Chomsky has put his finger on two problems that are, or should be, of interest to those trying to understand the nature of religious experience. On the one hand, there is “Plato’s problem,” the problem of understanding how it is that we can know so much with so little evidence. On the other hand, there is “Orwell’s problem,” the problem of understanding how it is that we can know so little with so much evidence. In this paper I will argue that language and power have a lot to do with what and how one comes to an understanding of religious studies.

My exploration into the language and politics of religious experience was prompted by a seemingly offhand remark by Paul Williams in Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. There, in a discussion of Bon’s relationship to Buddhism, Williams writes, “Furthermore, the old pre-Buddhist religion of Tibet…was not, as far as we can tell, shamanistic in any way” (188). That is, Williams claims that the Bon po religion came into being alongside the introduction of Buddhism into Tibet and that it was not a continuation of a pre-Buddhist Tibetan religion. This latter claim in itself strikes me as perfectly reasonable. However when Williams goes further and denies the shamanic nature of the Tibetan soil into which Buddhism was transplanted, then I feel impelled to address the issue of revisionism.

We should not think that such a pursuit is of marginal concern or a fool’s quixotic quest. We have already noted that we are dealing with a variation of “Orwell’s Problem,” knowing so little with so much evidence, so we must above all resist any tendency toward self-censorship, as the issue we’re dealing with is those ideological constraints on what can reasonably be questioned. One cannot speak against ideological constraints without, almost by definition, sounding too “radical.”

I have said that we are dealing with two problems: first, how can we know so much with so little evidence; and second, how can we know so little with so much evidence? But perhaps we should start with: How can we know anything at all? A short answer that is relevant here is offered by J.J Clarke in Oriental Enlightenment: The Encounter between Asian and Western Thought. There he sums up his hermeneutical method in the following way: “[W]e must avoid any supposition that we can enter into and fully recover the meanings and mentalities of past ages and their symbolic products. All knowing is historically grounded, which means that, though I can become aware of, and even critical of, this [or any] fact, I can never escape the historical conditions in which I think and write” (13). In other words, we know by interpretation. And as such, we much never forget, Clarke warns us, that our interpretation is permanently anchored in our point of view.

However, one problem is already apparent. It simply is not true that “all knowing is historically grounded.” Clarke, a victim of postmodernism, has by page 13 already overstated his case. Undoubtedly what he meant to say is that all “narratives and symbols” (the means by with ideas are communicated) are historically grounded. Because to say that “all knowing is historically grounded,” is already to deny the existence, or even the possibility, of eternal knowledge—the existence of which is the first claim of religion.

Such a denial is very fashionable, but is it true? Later, in answer to “Orwell’s problem,” I hope to show that such a denial is not only false, but obviously false. I am willing to grant that “eternal knowledge” is not an item of everyday experience, but then everyday experience is not all of what we are talking about when are speaking about religion. For example, here is how Geoffrey Samuel defines “shamanism” in his Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies:

This category of practices may be briefly described as the regulation and transformation of human life and human society through the use ( or purported use) of alternate states of consciousness by means of which specialist practitioners are held to communicate with a mode of reality alternative to, and more fundamental than, the world of everyday experience (his emphasis). (8)

Now this alternative mode of reality, which is more fundamental than everyday experience, is a clue that suggests that there is more to “knowing” than what is “historically grounded.” Humans may have different languages, cultures, and thus perspectives, but fundamentally they all have the same brains, physiology, chemistry, and nervous systems. And through the manipulation of such systems humans can enter into what I call non-discursive states of knowing. The implications for the understanding of “other” religions will be our answer to Plato’s Problem, or how we can know so much with so little evidence. But first we must break the silence and directly address Orwell’s Problem, or how we can know so little with so much evidence.

Tomoko Masuzawa appears to have had a presentiment of the problem. In his “In Search of Dreamtime: The Quest for the Origin of Religion,” he writes that the study of religion, as he found in America, is “intricately graced with an imposing network of rules and regulations,” and that, “in addition to the usual litany of general ethics of learning,” there is in religious studies a “remarkable profusion of warnings.” Masuzawa then adds: “I found one precept in particular more startling than any other. This is the dictum, ‘Thou shalt not quest for the origin of religion.’ It is as though our integrity as modern, factually responsible scholars of religion depended on our compliance with this fundamental vow, or rather, disavow” (qtd. in Olson 79). The phrase, “as though our integrity depended on our compliance,” is particularly interesting; because of course the integrity of the scholar depends on no such thing. The idea that integrity in the academy depends on adhering to unspoken rules is, as Masuzawa appears to have suspected, clearly an instance of double-speak, and should be of interest only to the thought police. But as long as war isn’t peace, ignoring the key facts isn’t being honest.

Obviously, when we talk of Orwell’s Problem we are talking about ideological constraints on what we can think and question. Here is how such constraints play out in the study of religion. If, for example, one were to find an ancient scroll in the desert belonging to the Zoroastrians, and whose content demonstrated distinct parallels with the Christian tradition, there would be a lot of interest (and rightly so) in finding out everything we can about that scroll and how it fits with the rest of our knowledge of the early Middle Eastern religions.

However, what if that scroll is about a plant, which in Zoroastrian tradition functions the same as Christ functions in Christianity? Would we still be interested in everything about the scroll? Would we, for example, be interested in the plant’s pharmacology? And if it turned out to be a mind-altering drug, would we be interested in its phenomenology? Would we seek to isolate the active compound to see how it affects those centers of the brain most implicated in the production of religious feelings and thoughts? Would anyone dare suggest eating the plant, to see if it at least feels transcendent or sacred in any way? Would anyone be interested in asking how Christ and a drug could play similar functional roles in related religious traditions?

Well, actually, no they wouldn’t. And we know they wouldn’t because our hypothetical situation is really a historical case study, and the fact of the matter is that no “serious thinker” has ever asked such questions.

Indeed, here is the same scenario as history and not hypothetical speculation. One can read it in Religions in Four Dimensions, where Kaufmann argues that Zarathrustra introduced a new and quicker path to heaven, “the Yasna, a word which literally means ‘sacrifice’’’ (Kaufmann 62). According to R.C. Zaehner, in “The Dawn and Twilight of Zoroastrianism,” Zarathrustra denounced the ancient sacrifices “in which a bull was slain and the fermented juice of a plant called Haoma consumed; yet it is precisely the drinking of the Haoma-juice which has for time immemorial constituted the central act of the Zoroastrian ritual” (qtd. in Kaufmann 62). Kaufmann continues to quote Zaehner as he argues for the influence of archaic religions in establishing patterns that we would be more comfortable thinking came out of a vacuum.

This sacrament provided a royal road to salvation and the juice itself—like Soma in the Vedas—was considered divine. As a god, it is Ahura Mazda’s son. “In the ritual, the plant-god is ceremonially pounded in a mortar; the god, that is to say, is sacrificed and offered up to his heavenly Father. . . After the offering, priest and faithful partake of the heavenly drink, and by partaking of it they are made to share in the immortality of the god. Zaehner concludes: “The conception is strikingly similar to that of the Catholic Mass.” (Kaufmann 62)

But again, the questions that weren’t pursued are the obvious ones. What is Haoma? Not to mention the really important one: “What is it like? That is, what is it like that it could play a role functionally similar to that of Jesus?”

In the West, we don’t mind knowing that the religions of China and India were founded on ancient shamanic practices; that knowledge is power, our power. It allows us to be “different” from them in a way that tacitly implies our superiority. In other words, our ignorance of the “shamanic” roots of our own culture serves an ideological function. It affords us the attitude that ours is the religion, the one that isn’t a mass of superstitions founded on drug-induced hallucinations.

Indeed, the same might be true of our philosophical roots also, for there is some reason to believe that Socrates was “corrupting the youth” by giving away the “secrets” of the Eleusinian Mysteries (see The Road to Eleusis: Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries, by R. Gordon Wasson, Carl A. P. Ruck, and Albert Hofmann). Plato obviously respected the esoteric/exoteric divide, but if it is true that the kykeon (an LSD-like drink made from ergot) of the Mysteries was implicated in Greek Philosophy, few “serious” scholars think it important. A possible exception, however, is J.N. Findlay who, according to Huston Smith, notes that:

The two following sentences from Plato’s Seventh Letter should be put at the head of every translation of Plato’s work: ‘The publicizing of those secrets [with which that letter is concerned] I do not deem a boon for men, excepting for those initiates who are able to discover them with no more than a given hint. For the others it would produce a stupid derision or else a self-glorification in a mistaken idea that they have eaten wisdom with spoons.’” (qtd. in Smith 41)

One unthinkable but obvious way of approaching this contention would be for serious scholars of Platonic philosophy to recreate, and actually drink, the kykeon to see if there is anything in the resulting state of consciousness, i.e., in its phenomenology and structure, which reflects the nature of Plato’s philosophy. Personally, I’ve always suspected that the “other world” of Platonic Thought refers to different states of mind. Certainly, Socrates is always falling in and out of “trances,” a fact that is never mentioned by polite students of Greek philosophy who insist on seeing him as the paragon of reason alone.

Yet, even the notion that the foundations of Chinese and Indian religions are “shamanic,” is rarely elaborated on. Apparently we of the Western intellectual tradition don’t want to know too much, just enough for our purposes. Indeed, in a related argument Mary Barnard has written that, “fifty theobotanists working for fifty years would make the current theories concerning the origins of much mythology and theology as out-of-date as pre-Copernican astronomy” (qt. in Smith 19). By now, however, it hardly needs mentioning that the revolution was canceled for lack of interest. But the questions remain: What is the “function” of, and in whose “interests” are we disavowing the search for origins?

In one answer to these questions, J.J. Clarke brings to us a vivid image from his Oriental Enlightenment, where he writes that: “Some have gone so far as to suggest that…the role of orientalists was little different from that of the geographers and surveyors who were part of the colonial retinue” (26). Clearly his own view, or the “main argument” of his book, is that “orientalism, even in its most academic guise, is inextricably bound up with Western concerns and problems, and only to a limited extent can be thought of in terms of a disinterested quest for knowledge” (22). A view, Clarke notes, which is a nuanced variation on Edward Said’s position that orientalism, “represents nothing less than the expression and justification of the global authority of the modern West” (22). My own answer is closer to that of Said’s. In short, what Orwell’s Problem reveals is that the project of understanding the nature of religion is not about the pursuit of truth but, instead, about gathering and maintaining power. Obviously, there is more to the prohibition on searching for the origins of religion, and we will come back to this issue, but first we must say a few words about Plato’s Problem, how is it that we can know so much with so little evidence, for I hope to show that the two problems are surprisingly inter-related.

As it concerns religion, Plato’s Problem has to do with “referents” and language. Much of my thinking here is a bit technical and this paper is not the place to develop it fully, but it might be enough to note that I take my view of language from Chomsky, which is to say that I don’t believe in a “public language” or in “wide content” (the belief that part of the meanings of words depends on any kind of external realism) or that words “rigidly designate” anything, as many analytical philosopher do. Nor do I believe in the “death of the author” or that words can only infinitely and indefinitely refer to more words, as many continental philosophers do. On the contrary, I think Chomsky is right; what we have is just experience encoded by the language faculty of the human mind/brain. Language is primarily a tool for human thought, and only secondarily for communication. Words don’t “refer” to anything; people refer to things with words. Thinking and language are not the same thing. What is “referred” to is experience, both internal and external, registered in the language faculty and remembered in the brain/mind. The meanings of words are mostly “innate.” And according to The Cambridge Companion to Chomsky, edited by James McGilvray, language could not have evolved through the mechanisms of natural selection but, instead, appears to have been “anticipated,” as Chomsky put it, and to have arisen, “‘by itself’ when other systems [of the brain] are in place” (McGilvray 7). In short, if my linguistic encoding is similar enough to yours then there is no problem with us communicating. But if our codes are different then the problems we might have in understanding each other is a function and a measure of just how different those codes are.

This is where hermeneutics comes in, and it is usually assumed that all meaning is historically grounded. But I disagree. Usually people who say that all meaning is historically grounded either ignore that some words refer to experience which is atemporal, and thus by definition eternal, or they deny that such ahistorical experience is possible. By “ahistorical” experience I mean experiences that are instantiated by the death of the ego and, in a Kantian sense, the collapse of our mental categories of time and space, which is concomittent with ego-death. In Chomskian terms, it might be described as a temporary distortion of certain innate concepts within the language faculty, which, by the way, would explain the ineffability of religious experience.

Nevertheless, most people who deny the possibility of experiencing and thus referring to, anything outside of time and space usually do so on the authority of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. However, those same people are usually forgetful of Kant’s discussion of sublime experience in his Critique of Judgment. There in his last critique Kant goes beyond his early writings and shows us how it is that, by the experience of the sublime, we know that we are “supersensible” beings. That is, with the experience of the sublime both our imaginative and our rational faculties (including the forms of time, space, and the famous categories of plurality, substance, causations, etc.) are superseded, leaving us with the realization of our “supersensible destination.” And so now the crucial question arises: What exactly is the sublime? Here is what Kant tells us:

The sublime is that in comparison with which everything else is small (his emphasis)….Nothing therefore, which can be an object of the senses is, considered on this basis, to be called sublime. …Consequently it is the state of mind produced by a certain representation with which the reflective judgment is occupied, and not the object, that is to be called sublime. (qtd. in Adams 393)

In other words the sublime is a certain “state of mind” that goes beyond the limits of our imaginative and rational faculties. Indeed, such a “state of mind” is sublime because, in Kant’s words:

[The] magnitude of a natural object on which the imagination fruitlessly spends its whole faculty of comprehension must carry our concept of nature to a supersensible substrate which lies at its basis and also at that basis of our faculty of thought. As this, however, is great beyond all standards of sense, it makes us judge as sublime, not so much the object, as our own state of mind in the estimation of it. (qtd. in Adams 394)

Notice that this state of mind—today we would call it an alternate state of consciousness—is a state of knowing that by definition is beyond our categories of time and space. Thus, contrary to Clarke and Gadamer, not all knowing is historically grounded. Furthermore, what is known in such a state is the “supersensible substrate” that underlies our cognitive faculties, and it is in knowing this supersensible substrate that the mental state is called sublime.

Narratives and symbols may be historically grounded, but neurobiology—not to mention the underlying innate concepts of the human language faculty—is for all intents and purposes constant across history and geography. Lately in the West we have been very fond of pointing to centrist distortions of all kinds; for example, writers have recently been accused of being Eurocentric, Logocentric, Phalocentric, and so on. But as far as I know, no one has yet pointed out the unjustified Western assumption that our mundane or everyday state of mind is the appropriate state from which to analyze the nature of consciousness and reality. This so far unnoticed and unnamed centrism is particularly startling given the fact that the majority of non-Western cultures have held the very opposite assumption. Our blind spot may be due to our unwillingness to acknowledge even the possibility that many yogis, meditation masters, Sufis, saints, and shamans have surpassed their sober European counterparts in describing the nature of what Kant called our “supersensible substrate.” However, it is in noting the possibility that Western philosophers of mind have a lot to learn from religion and non-western philosophies, which I think is a fact, that we run directly into Plato’s Problem of how we can know so much given so little evidence.

I will be arguing soon that what Kant called the “supersensible substrate” is roughly what the Buddhists and many others have called with some controversy Emptiness and/or Light. The key lies in knowing the referent, i.e. the state of mind, to which the word sublime refers. And that is not something one can do by simply reading a dictionary or any other sacred text alone. That is, we must, like good detectives, follow the trail to an examination of consciousness and its states. The reader should note that while I am writing about sublime states of mind, the writing itself can in no way substitute for what is learned from such states themselves. Therefore, without mistaking the finger for the moon, let us now turn to the states themselves.

To this affect, I don’t believe that one can do any better than to turn to the works of Stanislav Grof. Working with LSD, Grof has, to my knowledge, done the most extensive phenomenological research into alternate states of consciousness, some of which is relevant here to the study of religion and Plato’s Problem. For example, in The Cosmic Game: Explorations of the Frontiers of Human Consciousness, Grof notes that two main experiences are generally recognized as the end points of the “mystical and philosophical quest” (26). The first is that of “Light” which comes either as the “full light” or as “a cosmic thunderbolt” (27); the second is sometimes called the “Cosmic Void or Emptiness” (30). Students of religion everywhere recognize these words as present in many of the world’s religious texts and philosophies, but the question is do we know what their referents are? That is, do we know the sublime states of mind to which the words refer? If not, then we can only understand the meaning of the words by more reference to the various narratives in which they are embedded—and Plato’s Problem is no longer a problem because without knowledge or experience of the referent we don’t know enough to need justification for how much we know. There is no need to explain how the whole is greater than the sum of its parts if we aren’t aware of the whole. If we don’t know the atemporal referents to these key religious “signs,” then it would appear that all knowing is indeed historically grounded and that linguistic analysis and hermeneutics, even with their circles and limits, are our only tools for understanding “other” traditions. However if the researcher does know the mental states to which the symbols refer then Plato’s Problem becomes pressing. Indeed, here is how Plato’s Problem is played out in the study of religion.

A good example of someone who demonstrates knowledge of much with seemingly little evidence is Mircea Eliade. In an essay called “Experiences of Mystical Light,” in his The Two and The One, Eliade places the experience of Light as the central realization of all religions. In other words, every religion, according to Eliade, from Judaism to Hinduism, is a path that leads ultimately to the Light. It is also worth noting here that Eliade’s “Light” comes in differing degrees of roughly the same three varieties, namely, the Full Light, the Ray, and the Void, which Grof elucidates. That is, Eliade notes that there is a Light that, “blots out the surrounding world” (75), corresponding to Grof’s “Full Light,” and there is the “Column of Light” (51), corresponding to Grof’s “Thunder Bolt or Ray,” and, lastly, “there is the Light that transfigures the World without blotting it out” (75), which corresponds to Grof’s Void. However, we must quote Eliade at length if we wish to really get the flavor of his writing, and to understand why postmodernists—who fear that to step over “difference” is to step in the direction of “totalitarianism”—and also why analytical philosophers—who fear that such words as “Light” and “Void” do not actually “pick out” anything—would dismiss such claims by Grof and Eliade as cultural imperialism or literal non-sense:

It is important to stress that whatever the nature and intensity of an experience of the Light, it always evolves into a religious experience. All types of experience of the light that we have quoted have this factor in common: they bring a man out of his worldly Universe or historical situation, and project him into a Universe different in quality, an entirely different world, transcendent and holy. The structure of this holy and transcendent Universe varies according to a man’s culture and religion—a point on which we have insisted enough to dispel all doubt. Nevertheless they share this element in common: the Universe revealed on a meeting with the Light contrasts with the worldly Universe—or transcends it—by the fact that it is spiritual in essence, in other words only accessible to those for whom the Spirit exists. We have several times observed that the experience of the Light radically changes the ontological condition of the subject [a point to which Kant would agree] by opening him to the world of the Spirit [or the supersensible substrate and the intermediate states that lead up to it]. In the course of human history there have been a thousand different ways of conceiving or evaluating the world of the Spirit. That is evident. How could it have been otherwise? For all conceptualization is irremediably linked with language, and consequently with culture and history [i.e., “all conceptualization,” and not “all knowing” is historically grounded]. One can say that the meaning of the supernatural light is directly conveyed to the soul of the man who experiences it—and yet this meaning can only come fully to his consciousness clothed in a pre-existent ideology…. Yet there remains this fact which seems to us fundamental: whatever his previous ideological conditioning, a meeting with the Light produces a break in the subject’s existence, revealing to him—or making clearer than before—the world of the Spirit, of holiness and of freedom; in brief, existence as a divine creation, or the world sanctified by the presence of God. (77)

Clearly, in this conclusion Eliade is speaking freely and using his own preferred locutions, but the implication is plain. Light may be referred to as the Light of Jesus, of Allah, of Shiva, or of Buddha, and so on, but the Light itself is the same, just dressed in different language, and the implications of encountering it are roughly the same.

Plato’s Problem, therefore, is how does Eliade, for example, know that there is basically one “Light” shared by all religions; after all, the religious texts themselves, which many hold as abundant evidence to the contrary, never say that their Light is the same as that of the religions next door.

Postmodernists would doubtlessly see in Eliade’s words only hegemony, usurpation of “the Other,” and the establishment of a purely Western pseudo-Christian meta-narrative. And, moreover, they would be right. After all, Eliade didn’t say, “…the world sanctified by the presence of Allah.” Analytical philosophers, in contrast, would doubtlessly see only non-sense words referring to nothing but objects of someone’s imagination. And they too would be right, at least so far as such words do not refer to any intentional objects or natural kinds. However, both groups miss the point. Eliade’s language can be used to include and empower, as easily as it can be used to exclude and disempower. And, as Kant noted, it is not an “object” of consciousness but a “state of mind” that is at issue here. Nor should it pass unnoticed that Eliade’s comments can be read as deflationary towards modern Western philosophy in that they do not assume that western scholarship is in sole possession of the truth, if indeed what you emphasize as most important in his analysis is the recognition of the Light itself and not the analysis as such.

My argument, in contrast to that of modern philosophy, is that we know the ahistorical and transcultural nature of “Light” by knowing the referent, which is to say, by knowing the sublime experience itself. Simply put, if one personally knows what the word Light refers to then one can, for example, know what Jewish, Shaivite, or Zen discussions of Light are about. But if one, for lack of experience, does not personally know the referent, then indeed one has no alternative but to run around in hermeneutical circles or run through the numerous possible worlds in which Light might refer to some natural kind. Nor am I trying to obfuscate the fact that delusion, the possibility of believing one has “seen the Light” when really one was only hallucinating, is a real concern. But ironically the possibility of delusion appears to be a real concern that all religions have in common, while, in contrast, neither the Continental nor the Analytical philosophers even address it.

Furthermore, I recognize that there are serious problems in my argument that Eliade is entitled to his claim that the world’s religions universally recognize and privilege the existence of Light. My case depends on the assumption, which I cannot prove, that Eliade has indeed experienced the Light within himself and thus knows what it means. Without at least having read Eliade’s personal biography, I cannot make my case here without assuming what I’m trying to prove.

Therefore, I have, with some reservations, opted to illustrate an example of Plato’s Problem with my own experience. When my friend and former Theravedan monk Chris first came back from Thailand and India, he and I had many debates about the relationship between Emptiness and Light. Chris had had an experience of Emptiness, which lasted about a week, while he was staying at the ashram of Sri H.W.L. Poonja in India (he had spend the previous two years in a forest monastery in Thailand). While Chris was away, I had had, in the span of one day (July 7, 1994—I know the date because I wrote it in the book I had just finished reading, Fuzzy Thinking: The New Science of Fuzzy Logic, by Bart Kosko), an experience of Light, preceded briefly by an experience of Emptiness, preceded by a symbolic realization of God, which in turn had been preceded by a vision of the Virgin Mary (I’m fundamentally what my priest calls a “bad Catholic”). Incidentally, it was this experience that shifted my interest from science to philosophy and religion. A key point for me is that for about a year after the experience and before Chris came home, I thought of it in basically Western terms. The various layers of my experience I had simply accepted as reflecting the richness of the Beatific Vision. I had for a long time no words to convey what happened in detail. It was only after talking to Chris that I learned a vocabulary rich enough to convey my experience unambiguously. So in my case, I had come to a knowledge of the referents in question before knowing the words for them, a fact which alone should make us pause. The point here, however, is that Chris and I both had similar experiences which precipitated years of debate about the relationship between Emptiness and Light.

Now here is how my experience pertains to Plato’s Problem. Take, for example, Giuseppe Tucci’s discussion of the Light and the Void in The Religions of Tibet, where he writes that the different schools of Tibetan Buddhism diverge on the question of the relationship between the Light and the Void, and, furthermore, their respective relationships to the mind. (64) Although he adds that, “this is not the place to enter into the subtle debates set off by this problem,” he does gives us a little sample: “According to the view of the Sa skya pa school luminosity is the characteristic sign of the mind, while the essence of the mind is voidness. Voidness does not detract from luminosity, nor does luminosity detract from voidness…[However] luminosity and voidness are not derivable from one another, but they flow together” (65). Now the question is, can anyone who is not deeply familiar with Tibetan Buddhist philosophy and religion know anything of substance concerning these issues dividing the various Tibetan schools? Certainly, there is very little evidence given in English language texts concerning this issue. Yet when I read Tucci, I’m convinced that I understand at least what the debates are about, even if I have never read their arguments, because I can understand how it is that the Sa skya pa could take their position. As it is, I do not find the Sa skya pa position as insightful as that of, say, the rNying ma pa. And my own characterization is that the realization of Emptiness is a matter of degree where at complete Emptiness there occurs a phase-change from a consciousness void of all ego-structures, one of pure subjective awareness, to an experience of the all-Light, or pure consciousness in itself.

The question for Western philosophers is how can someone as ignorant of Tibetan Buddhism as I was (and still am, though to a lesser degree) know anything substantial of Tibetan religion. This is Plato’s Problem. The answer I’m advancing is that the Tibetans are not, when talking about the Light and the Void, talking about something that is the sole purview of the Tibetan language or culture. Indeed, they are talking about states of consciousness that, literally, anyone with a brain can potentially experience and understand. If someone has had the pertinent experiences then she knows the referents to the key esoteric symbols and can unlock much of the most alien of symbols, narratives, and arguments. The confusing paradox is that one cannot find those referents by reading more texts; one can only find them in one’s own experience of different states of consciousness. In other words, the answer to Plato’s Problem is that we can know more than is warranted by the study of pivotal symbols and texts alone by knowing the meaning of the referents which gave rise to those signs in the first place.

With that said, we can now look again at Orwell’s Problem. There we noted that there are some things, like the relationship between drugs and religion, that we must be careful not to understand. Because to do so would be to jeopardize our self-definition as a civilization founded on a unique and personal revelation from God. Moreover, Orwell’s Problem reveals that the need for such a “unique” self-definition serves mainly the interests of power and the purposes of cultural hegemony, and not the pursuit of knowledge and truth. The only alternative and answer to Orwell’s Problem is for those working in religious studies and philosophy to resist, as Orwell himself put it, the “automatic action to lift the flap of the nearest memory hole.”

I should point out the inter-related nature of Orwell’s and Plato’s Problems. By ignoring Orwell’s Problem we ensure that we do not recognize, let alone solve, Plato’s. In other words, we are unmotivated to solve Plato’s Problem—to study alternative states of consciousness alongside the religious and philosophical language—if we do not first acknowledge that we already know that alternative states of consciousness are deeply implicated in the origins of religion and thus the formation of the various religious narratives, symbols, practices, and so on, which we do deign to study.

Lastly, there are many relevant issues that I wish we had more time to explore here: for example, the fact that experiencing the numinous without the scaffolding of sacred language runs counter to religious ends and goals; or the fact that some Tibetans reserve the use of entheogens for initiation rites. Nor have I had time to address the “war on drugs,” a pink elephant that I have chosen to ignore. Instead, I will conclude with some last remarks on the need for a new meta-language in which to discuss the various religious narratives of Light and so on.

I have argued that Chomsky’s view of language is useful for combating the distortion which Analytical and Continental philosophy brings to the study of religious texts. However, if words like “Light,” “Void,” “Soul,” “Spirit,” and in some cases even “God,” cannot be adequately thought about in terms of direct reference theory nor in terms of strong textualism, then we still have a need for categorizing such words. I propose we see them as members of a unique existential-aesthetic vocabulary, or existhetic vocabulary for short. Such words can be seen as existhetic in that they refer to powerful aesthetic experiences which undoubtedly alter the way one experiences the nature of one’s own being. With this understanding we could continue the tradition of linguistic and textual analysis without doing so much violence to the intended meaning of religious narratives. Indeed, the project analyzing existhetic language is one that I hope to pursue further at some future date.

Works Cited

Clarke, J.J. Oriental Enlightenment: The Encounter Between Asian and Western Thought. London: Routledge, 1997.

Eliade, Mircea. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstacy. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1964.

Grof, Stanislav. The Cosmic Game: Explorations of the Frontiers of Human

Consciousness. New York: SUNY, 1998.

Kant, Immanuel. “Critique of Judgement.” Critical Theory Since Plato. Ed. Hazard Adams. New York: HBJ, 1971. 377-399.

Kaufmann, Walter. Religions in Four Dimensions: Existential, Aesthetic, Historical,

Comparative. New York: Reader's Digest, 1976.

Kosko, Bart. Fuzzy Thinking: The New Science of Fuzzy Logic. New York: Hyperion, 1993.

Masuzawa, Tomoko. “From In Search of Dreamtime: The Quest for the Origin of Religion.” Theory and Method in The Study of Religion: A Selection of Critical Readings. Ed. Olson, Carl. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2003.

McGilvray, James. Ed. “Introduction.” The Cambridge Companion to Chomsky. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005.

Samuel, Geoffrey. Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies. Washington:

Smithsonian, 1993.

Smith, Huston. Cleansing The Doors of Perception: The Religious Significance of

Entheogenic Plants and Chemicals. New York: Tarcher-Putnam, 2000.

Tucci, Giuseppe. The Religions of Tibet. Trans. Geoffrey Samuel. Berkeley: California UP, 1980.

Wasson, R. Gordon, Carl A.P. Ruck, and Albert Hoffmann. The Road to Eleusis:

Unveiling the Secret of the Mysteries. New York: Wolff-Harcourt, 1978.

Williams, Paul. Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. London: Routledge, 1989.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

I recently came across your blog and have been reading along. I thought I would leave my first comment. I don't know what to say except that I have enjoyed reading. Nice blog. I will keep visiting this blog very often.

http://www.pinellaswindowsanddoors.com/

Post a Comment