GOD AS AN INSTITUTIONAL FACT:

A NEW APPROACH TO THE QUESTION OF GOD’S EXISTENCE

Abstract: In my paper, “God as an Institutional Fact,” I have tried to adapt the vocabulary used by John R. Searle in making distinctions between different kinds of reality. My demonstration is based on the argument that “God” meets Searle’s three conditions for the establishment of institutional facts, namely, collective intentionality, constitutive rules, and the assignment of function. In meeting this last condition I draw heavily from the works of the anthropologist Roy A. Rappaport and the archaeologist Brian Hayden. My hopes for this paper are twofold. My first hope is to provide a new way of thinking about God, about its nature and role, a way which relies neither on the ideas of substance nor process. My second, and most ambitious hope, is that the understanding of God described here is one that can be accepted both by religious and non-religious thinkers alike.

The philosopher John R. Searle notes that there are two kinds of epistemologically objective facts: ontologically subjective facts, like money and political borders, which have an observer-relative existence; and ontologically objective facts, like gravity and photosynthesis, which have an observer-independent reality. Furthermore, there are also facts, like thirst, pain, and other mental/physical states, which by virtue of having both an ontologically subjective and an ontologically objective ontology, i.e., both a first-person and a third-person ontology, can be said to be both observer-relative and observer-independent. By utilizing the vocabulary developed by Searle for dealing with different kinds of facts and different kinds of reality this paper attempts to argue for the epistemological objective reality of God as an established institutional fact with at least an ontologically subjective reality.

According to Searle, a social fact is simply, “any fact involving two or more agents who have collective intentionality,” regardless of whether or not the agents are capable of using a language (121). Institutional facts, in contrast, are built up from social facts. Only agents with language can establish institutional facts. The other conditions, besides merely thinking, needed to establish institutional facts Searle calls collective intentionality, constitutive rules, and the assignment of function. We will have to understand these conditions before we can see how they apply to the existence of God.

First, we must understand that the notion of “collective intentionality” does not violate the standards of methodological individualism; the term does not refer to any mental entities that exist outside of individual people. Instead, all collective intentionality means is that we individual human beings sometimes have intentional mental states of the form “we-intend,” as well as those of the form “I-intend” (119). For example, members of a soccer team can work together to score goals only because they each have in their minds the intentional state of we-intend to work together to score goals.

The second condition of an institutional fact is that it must be made up of constitutive rules. That is, institutional facts must be made up of rules that constitute behavior. For example, following the rules of chess constitutes playing chess. Constitutive rules are to be contrasted with rules that only regulate an activity. One can play with the chess pieces on the chess board without following the rules of how the pieces are to be moved; however that does not constitute the game of chess. In contrast, following the rules of the road only regulates the way one drives but does not constitute driving. Indeed, most people could figure out how to drive a car without ever learning the rules that regulate it (123). Interestingly, such constitutive rules themselves always have the logical form of, “X counts as Y in (context) C.” For example, in a soccer game kicking the ball into the other team’s net counts as scoring one point for your team. The difference between an institutional fact, such as what counts as a goal in soccer, and a brute fact, such as the fact that gravity keeps me on the surface of the Earth, is that “institutional facts only exist within systems of such [constitutive] rules” (123).

The third condition that we must satisfy in order to recognize that the existence of God is an epistemologically objective institutional fact with a subjective ontology is that of “the assignment of function” (121). The point to be gathered here is simply that, “all functions are observer-relative,” in that only agents can assign a function to natural objects and causal processes. For example, Searle notes that we can say that the function of a heart is to pump blood but only once we, the agents, have presupposed that “life and survival are to be valued.” Thus “all functions are observer-relative” and “never observer independent.” Indeed, according to Searle, “What function adds to causation is normativity or theology. More precisely the attribution of function to causal relations situates causal relations within a presupposed theology” (122). In other words, the assignment of function also introduces normativity by allowing us to talk about better or worse functions. In another example given by Searle, “primitive peoples” assign the function of digging to a stone. Once they have assigned stones a function, then they can value the stones they are looking for as better or worse stones (121). The two points, or two sub-criteria of this third condition to keep in mind here are, first, that it is by exploiting the natural features of an object for our purposes that we come to the assignment of function (121) and, second, that such an assignment allows us to ask if there are better or worse hearts/pumps, stones/digging tools, and so on.

Finally, and before looking closer at how God came to be objectively real as an institutional fact of our social reality, let us look at how the three conditions for the invention of such facts—collective intentionality, constitutive rules, and the assignment of function—work together to create real ontologically subjective but epistemologically objective facts. The most apropos example that Searle gives us of how the three conditions work to establish institutional facts is that of “the wall.” Searle invites us to “imagine a group of primitive creatures more or less like ourselves,” who have come together as a group to build a rock wall around their living area. This wall then functions, by virtue of its physical characteristics, as a border between the group’s living space and that of others. However, as the wall begins to erode with time, and if the following generations continue to see that line as the border but do not actually rebuild the wall, then the line once marked by that wall will continue to be an objectively real border. (125) This “shift” from the wall functioning by “virtue of its physical features” to it functioning by “virtue of the collective acceptance or recognition” is what establishes institutional facts. Furthermore, all institutional facts have what Searle calls “status functions” (126). That is, money, to use another of Searle’s examples, is money because it has the status of being money, not by virtue of its physical features, which, after all, can be counterfeited , and which in the modern world, no longer have any particularly valuable physical properties.

Now with the above conceptual framework in place we can begin to utilize it in our search for a clearer understanding of the nature and role that God has in our modern world. My thesis is that God is indeed an institutional fact, and that like such facts God is not only mind-dependent with an ontologically subjective existence, but also (and most surprisingly) real in an epistemologically objective sense. If my thesis is correct, to categorically deny the existence of God is to be factually in error. Therefore, we must see how God fulfills Searle’s conditions for the establishment of institutional facts.

With regard to collective intentionality, it is enough to note that enough members of American society have in their minds/brains the intentional state of we-intend to be one nation under God to meet the first condition. Furthermore, one could also note that there are enough members of congregations with the mental state of we-intend to worship God as a group, and so on.

An example of a system of constitutive rules in which God as an institutional fact is embedded might be the conditions under which sworn oaths are accepted as binding. That is, traditionally swearing an oath on the Bible to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth counts as a public recognition of God’s reality as a condition for binding promises in the context of American society. Of course this means that it does not matter if children, citizens, or presidents believe in God or not; from an institutional perspective, putting one’s hand over one’s heart, or on a Bible, while making a promise to God constitutes the existence of God as an epistemologically objective institutional fact to which one swears. If we forget for the moment the necessity of having the first condition, then we could say that if tomorrow everyone stopped believing in God, but kept pledging allegiance to one nation under God, or swearing to God to uphold the laws, and so on, then they would all be wrong in their belief that God does not exist, at least as an institutional fact. To say that the green piece of paper in one’s pocket is not really money while still using it as money is not to understand what it is that makes money money.

In respect to meeting the third condition, the assignment of function, I have drawn heavily from the work of the anthropologist Roy A. Rappaport and the archaeologist Brian Hayden. Both argue, from different directions, that the function of God is to sanctify the social order and structure of our society. However, before demonstrating how the works of Rappaport and Hayden allow us to satisfy Searle’s third condition, we must first bear in mind that the appropriate “assignment of function” for the institutional fact of God’s existence must, by analogy to the history of other institutional facts like money and borders, also reflect the process by which some physical characteristic has been “eroded away” to leave only a pure status function. In other words, we must remember that such a function must meet two sub-criteria: first, it must have achieved its function by virtue of its physical features (i.e., reducible to physics, biology, or chemistry), which later “eroded” away leaving only the status function behind (like the precious metals and physical obstacles that once constituted money and borders but which are no longer necessary); and second, it must introduce normativity in the same way that assigning a function to hearts introduces the notion of there being “better or worse hearts.” As noted in Rappaport’s work, the function of any god or “Ultimate Sacred Postulate” is to unite and sanctify the order of a society (346). Therefore, it appears that there are also better or worse gods depending on how well they serve this function.

The first sub-criteria or the physical features from which God as an institutional fact originally derived the function of uniting and sanctifying the order of society were, I propose, certain kinds of ecstatic brain states, or what Hayden calls “sacred ecstatic experiences” (63). In other words, the physical feature I am proposing is a special kind of brain state, sometimes referred to as a mystical or religious experience, such as those derived from the biological and chemical transformations of human neuro-physiology during the most archaic kinds of religious rituals; for example, those involving long sustained periods of drumming, chanting, dancing, fasting, praying, drug-taking, and so on. My proposal is in line with both Rappaport (220 & 229) and Hayden (63). Note that such activities are thought by Rappaport (323) and Hayden (28) to have predated the existence of language, and that Searle speculates that our cavemen wall builders were also pre-linguistic. Thus, it seems, it is not necessary to presuppose the existence of a god in order to create rituals of ecstatic brain states any more than it is necessary to presuppose the existence of a border in order to create a wall. In this respect, ecstatic mental states of the brain stand in the same historical relationship to God as Searle’s caveman wall stands to, say, international borders. In the vocabulary that I am about to introduce, we could say that the numinous pre-existed the sacred before the numinous was eroded away by civilization.

Indeed, this relationship between a special physical state of the brain and the institutional fact of God’s existence is described in detail in Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity (2002), although Rappaport does not characterize the relationship in these terms. Instead, he modifies the vocabulary of Rudolf Otto. For example, Rappaport understands “the Holy” in a very limited way of comprising of two main features, namely, the sacred and the numinous (290). The sacred is the speakable half of the Holy such that utterances like “God,” “Allah,” “the Buddha,” and so on, can be seen as “Ultimate Sacred Postulates,” and are the pentacle of an interconnected hierarchy of religious utterances ( 377). The numinous, in contrast, is the ineffable half of the Holy, of which nothing can properly be said. And most importantly for our case, Rappaport points out that the numinous half of the Holy has become conspicuously absent, or eroded away, from modern religions leaving only the sacred language behind (448). Again, Rappaport, as if he wanted to help me draw even tighter my analogy to Searle’s wall—the numinous is to “the wall” as God is to the border— argues that the numinous half of the Holy most likely predated language.

This crucial first sub-criteria for establishing God as an institutional fact, i.e., an epistemologically objective reality with a subjective ontology, can also be addressed from a different and less theoretical angle: The work of the archaeologist Brian Hayden, Shamans, Sorcerers, and Saints: A Prehistory of Religion (2003), provides overwhelming archaeological evidence for Hayden’s thesis that civilization has for the most part eroded “ecstatic religious experience,” away from modern life. Hayden claims, “it is precisely the earthshaking emotional experiences created in ecstatic religious rituals that were adaptive…. [as] a means of emotionally bonding people together” ( 31). Indeed, what he demonstrates in his work is that the priority of the numinous over the sacred remained virtually unchanged for hundreds of thousands of years in the prehistory of religion—which was marked by an unrestricted access to participation in religious states of consciousness—before it began to be eclipsed in the history of religion—which is also the history of religious elitism and exclusivity (147). Like Rappaport, Hayden suggests that it was the power of religious states of consciousness, or in other words, the power of participation in the numinous, to forge belief systems that override even biological survival instincts and commitments of families and clans that is largely responsible for the role that culture has now come to play in the life of the human animal (32).

However, with regard to normativity, or the second sub-criteria, the important thing here is that both Rappaport (407) and Hayden ( 44) assign an adaptive function to God, which allows us to ask, are some religions, gods, or Ultimate Sacred Postulates, better or worse than others? Obviously the answer is yes if the normative function of sanctifying, ordering, and uniting societies through the establishment of Ultimate Sacred Postulates as institutional facts is an adaptive feature of our societies. Actually, according to Hayden, ecstatic religious experience, or the numinous as Rappaport calls it, was a key adaptive feature of our species “for more that 99.5 percent of human existence,”( 22 & 31) and its demise has left us with “the book religions” as a kind of empty shell (4). But regardless of what we may think of Hayden’s characterization of religion, the evidence he provides for his thesis is also evidence that supports our claim that God is an institutional fact whose pure status function is the result of the erosion of certain mental/brain states from our modern experience, which, of course, is not to say that God is not real, but rather it is to demand that we accept and deal with the fact that God is at least as objectively real as borders and money.

Nor is it the case, as I pointed out in the introduction, that the two categories of the ontologically subjective and the ontologically objective are mutually exclusive; to establish the existence of the subjectively real ontology of God is not to deny that she might also have an objective ontology, which allows Searle to explain that, “Consciousness and intentionality, though features of the mind, are observer-independent in the sense that if I am conscious or have an intentional state such as thirst, those features do not depend for their existence on what anyone outside me thinks (94).

Thus, there is also a third ontological possibility of something having both an objective and a subjective ontology. Thirst, hunger, and, one could argue, ecstatic states of mind/brain, are all ontologically objective because they are biological states with intrinsic intentionality and they are ontologically subjective because only the experiencer can subjectively experience his or her objectively real thirst.

Thus, one could possibly argue an alternative thesis to the one stating that God is an institutional fact, proposing instead some version of the “Holy” where a real god is necessarily a union of the numinous and the sacred. One could perhaps further argue that at one time God also had an ontologically objective aspect, in the way that invisible political borders were at one time marked by visible physical barriers. In that case, we are no longer dealing with an analogy to international borders, but rather to some version of the Nietzschean idea that we have somehow killed God by eroding away its essence. Yet whatever the truth may be about God and this third possibility—maybe the union of subjective and objective ontology is all that should be meant by “the Holy”—I do not know. But one thing should be clear, for better or worse: The existence of God is an established fact.

Lastly, I feel I must say a few words about the political implications of my thinking about God as an institutional fact. My personal conclusions are hard even for myself to accept. I find them painful to admit and so I will state them succinctly and hope that I am wrong in my assessment. Basically, if God is an undeniable institutional fact necessary for the unified and coherent social body, then such a discovery spells bad news for everyone. Old-school Leftists who want to address social, political, and economic problems without acknowledging the necessary role for God to play in their humanistic solutions, will be as unhappy with the state of affairs sketched above as the to followers of the new religious Right, who will find that salvation is not assured simply because God is real. On an international scale, it is hard to imagine any Ultimate Sacred Postulate that could become real enough, as an ultimate institution fact, to hang any authentic World Order.

NOTES

It should be clear, from the perspective we are taking, that what is true of God is also true of Allah, Yahweh, and any other god whose existence is still currently an institutional fact. That is, in classrooms, courtrooms, Congress, and at Presidential inaugurations the pledges and oaths are made to the gods whose realities are still currently established as institutional facts, and not to those like Zeus or Mithra whose realities have evaporated along with the institutions that once established them.

This notion of false money as “counterfeited” is, I believe, analogous to “made up religions,” for example, the one I made up when I was a child. I could try to pass it on by converting others, but it would still be a false religion.

Rappaport lists two aspects to the Holy beside the sacred and the numinous, namely, the occult, and the divine. “The term ‘occult’ refers to religion’s peculiar efficacious capacities and the ‘divine’ will signify its spiritual referents” (Rappaport 24).

REFERENCES

Hayden, Brian.

2003 Shamans, Sorcerers, and Saints: A Prehistory of Religion. Smithsonian Books: Washington D.C.

Rappaport, Roy A.

2002 Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity. Cambridge UP: United Kingdom.

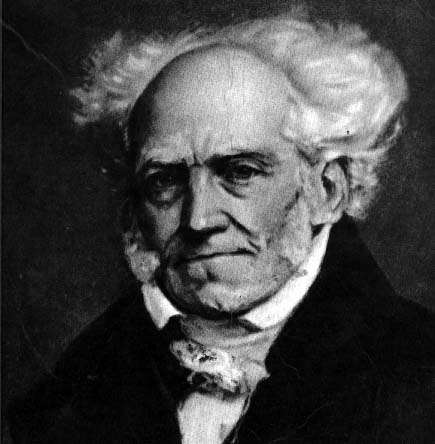

Searle, John R.

1999 Mind, Language and Society: Philosophy in the Real World. New York: Basic Books.

Thursday, March 15, 2007

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)