GOD AS AN INSTITUTIONAL FACT:

A NEW APPROACH TO THE QUESTION OF GOD’S EXISTENCE

Abstract: In my paper, “God as an Institutional Fact,” I have tried to adapt the vocabulary used by John R. Searle in making distinctions between different kinds of reality. My demonstration is based on the argument that “God” meets Searle’s three conditions for the establishment of institutional facts, namely, collective intentionality, constitutive rules, and the assignment of function. In meeting this last condition I draw heavily from the works of the anthropologist Roy A. Rappaport and the archaeologist Brian Hayden. My hopes for this paper are twofold. My first hope is to provide a new way of thinking about God, about its nature and role, a way which relies neither on the ideas of substance nor process. My second, and most ambitious hope, is that the understanding of God described here is one that can be accepted both by religious and non-religious thinkers alike.

The philosopher John R. Searle notes that there are two kinds of epistemologically objective facts: ontologically subjective facts, like money and political borders, which have an observer-relative existence; and ontologically objective facts, like gravity and photosynthesis, which have an observer-independent reality. Furthermore, there are also facts, like thirst, pain, and other mental/physical states, which by virtue of having both an ontologically subjective and an ontologically objective ontology, i.e., both a first-person and a third-person ontology, can be said to be both observer-relative and observer-independent. By utilizing the vocabulary developed by Searle for dealing with different kinds of facts and different kinds of reality this paper attempts to argue for the epistemological objective reality of God as an established institutional fact with at least an ontologically subjective reality.

According to Searle, a social fact is simply, “any fact involving two or more agents who have collective intentionality,” regardless of whether or not the agents are capable of using a language (121). Institutional facts, in contrast, are built up from social facts. Only agents with language can establish institutional facts. The other conditions, besides merely thinking, needed to establish institutional facts Searle calls collective intentionality, constitutive rules, and the assignment of function. We will have to understand these conditions before we can see how they apply to the existence of God.

First, we must understand that the notion of “collective intentionality” does not violate the standards of methodological individualism; the term does not refer to any mental entities that exist outside of individual people. Instead, all collective intentionality means is that we individual human beings sometimes have intentional mental states of the form “we-intend,” as well as those of the form “I-intend” (119). For example, members of a soccer team can work together to score goals only because they each have in their minds the intentional state of we-intend to work together to score goals.

The second condition of an institutional fact is that it must be made up of constitutive rules. That is, institutional facts must be made up of rules that constitute behavior. For example, following the rules of chess constitutes playing chess. Constitutive rules are to be contrasted with rules that only regulate an activity. One can play with the chess pieces on the chess board without following the rules of how the pieces are to be moved; however that does not constitute the game of chess. In contrast, following the rules of the road only regulates the way one drives but does not constitute driving. Indeed, most people could figure out how to drive a car without ever learning the rules that regulate it (123). Interestingly, such constitutive rules themselves always have the logical form of, “X counts as Y in (context) C.” For example, in a soccer game kicking the ball into the other team’s net counts as scoring one point for your team. The difference between an institutional fact, such as what counts as a goal in soccer, and a brute fact, such as the fact that gravity keeps me on the surface of the Earth, is that “institutional facts only exist within systems of such [constitutive] rules” (123).

The third condition that we must satisfy in order to recognize that the existence of God is an epistemologically objective institutional fact with a subjective ontology is that of “the assignment of function” (121). The point to be gathered here is simply that, “all functions are observer-relative,” in that only agents can assign a function to natural objects and causal processes. For example, Searle notes that we can say that the function of a heart is to pump blood but only once we, the agents, have presupposed that “life and survival are to be valued.” Thus “all functions are observer-relative” and “never observer independent.” Indeed, according to Searle, “What function adds to causation is normativity or theology. More precisely the attribution of function to causal relations situates causal relations within a presupposed theology” (122). In other words, the assignment of function also introduces normativity by allowing us to talk about better or worse functions. In another example given by Searle, “primitive peoples” assign the function of digging to a stone. Once they have assigned stones a function, then they can value the stones they are looking for as better or worse stones (121). The two points, or two sub-criteria of this third condition to keep in mind here are, first, that it is by exploiting the natural features of an object for our purposes that we come to the assignment of function (121) and, second, that such an assignment allows us to ask if there are better or worse hearts/pumps, stones/digging tools, and so on.

Finally, and before looking closer at how God came to be objectively real as an institutional fact of our social reality, let us look at how the three conditions for the invention of such facts—collective intentionality, constitutive rules, and the assignment of function—work together to create real ontologically subjective but epistemologically objective facts. The most apropos example that Searle gives us of how the three conditions work to establish institutional facts is that of “the wall.” Searle invites us to “imagine a group of primitive creatures more or less like ourselves,” who have come together as a group to build a rock wall around their living area. This wall then functions, by virtue of its physical characteristics, as a border between the group’s living space and that of others. However, as the wall begins to erode with time, and if the following generations continue to see that line as the border but do not actually rebuild the wall, then the line once marked by that wall will continue to be an objectively real border. (125) This “shift” from the wall functioning by “virtue of its physical features” to it functioning by “virtue of the collective acceptance or recognition” is what establishes institutional facts. Furthermore, all institutional facts have what Searle calls “status functions” (126). That is, money, to use another of Searle’s examples, is money because it has the status of being money, not by virtue of its physical features, which, after all, can be counterfeited , and which in the modern world, no longer have any particularly valuable physical properties.

Now with the above conceptual framework in place we can begin to utilize it in our search for a clearer understanding of the nature and role that God has in our modern world. My thesis is that God is indeed an institutional fact, and that like such facts God is not only mind-dependent with an ontologically subjective existence, but also (and most surprisingly) real in an epistemologically objective sense. If my thesis is correct, to categorically deny the existence of God is to be factually in error. Therefore, we must see how God fulfills Searle’s conditions for the establishment of institutional facts.

With regard to collective intentionality, it is enough to note that enough members of American society have in their minds/brains the intentional state of we-intend to be one nation under God to meet the first condition. Furthermore, one could also note that there are enough members of congregations with the mental state of we-intend to worship God as a group, and so on.

An example of a system of constitutive rules in which God as an institutional fact is embedded might be the conditions under which sworn oaths are accepted as binding. That is, traditionally swearing an oath on the Bible to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth counts as a public recognition of God’s reality as a condition for binding promises in the context of American society. Of course this means that it does not matter if children, citizens, or presidents believe in God or not; from an institutional perspective, putting one’s hand over one’s heart, or on a Bible, while making a promise to God constitutes the existence of God as an epistemologically objective institutional fact to which one swears. If we forget for the moment the necessity of having the first condition, then we could say that if tomorrow everyone stopped believing in God, but kept pledging allegiance to one nation under God, or swearing to God to uphold the laws, and so on, then they would all be wrong in their belief that God does not exist, at least as an institutional fact. To say that the green piece of paper in one’s pocket is not really money while still using it as money is not to understand what it is that makes money money.

In respect to meeting the third condition, the assignment of function, I have drawn heavily from the work of the anthropologist Roy A. Rappaport and the archaeologist Brian Hayden. Both argue, from different directions, that the function of God is to sanctify the social order and structure of our society. However, before demonstrating how the works of Rappaport and Hayden allow us to satisfy Searle’s third condition, we must first bear in mind that the appropriate “assignment of function” for the institutional fact of God’s existence must, by analogy to the history of other institutional facts like money and borders, also reflect the process by which some physical characteristic has been “eroded away” to leave only a pure status function. In other words, we must remember that such a function must meet two sub-criteria: first, it must have achieved its function by virtue of its physical features (i.e., reducible to physics, biology, or chemistry), which later “eroded” away leaving only the status function behind (like the precious metals and physical obstacles that once constituted money and borders but which are no longer necessary); and second, it must introduce normativity in the same way that assigning a function to hearts introduces the notion of there being “better or worse hearts.” As noted in Rappaport’s work, the function of any god or “Ultimate Sacred Postulate” is to unite and sanctify the order of a society (346). Therefore, it appears that there are also better or worse gods depending on how well they serve this function.

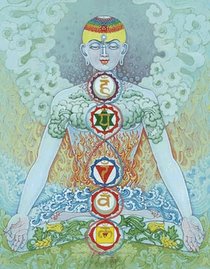

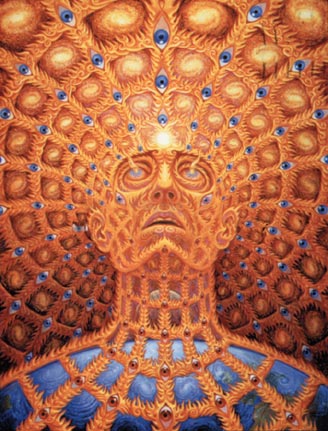

The first sub-criteria or the physical features from which God as an institutional fact originally derived the function of uniting and sanctifying the order of society were, I propose, certain kinds of ecstatic brain states, or what Hayden calls “sacred ecstatic experiences” (63). In other words, the physical feature I am proposing is a special kind of brain state, sometimes referred to as a mystical or religious experience, such as those derived from the biological and chemical transformations of human neuro-physiology during the most archaic kinds of religious rituals; for example, those involving long sustained periods of drumming, chanting, dancing, fasting, praying, drug-taking, and so on. My proposal is in line with both Rappaport (220 & 229) and Hayden (63). Note that such activities are thought by Rappaport (323) and Hayden (28) to have predated the existence of language, and that Searle speculates that our cavemen wall builders were also pre-linguistic. Thus, it seems, it is not necessary to presuppose the existence of a god in order to create rituals of ecstatic brain states any more than it is necessary to presuppose the existence of a border in order to create a wall. In this respect, ecstatic mental states of the brain stand in the same historical relationship to God as Searle’s caveman wall stands to, say, international borders. In the vocabulary that I am about to introduce, we could say that the numinous pre-existed the sacred before the numinous was eroded away by civilization.

Indeed, this relationship between a special physical state of the brain and the institutional fact of God’s existence is described in detail in Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity (2002), although Rappaport does not characterize the relationship in these terms. Instead, he modifies the vocabulary of Rudolf Otto. For example, Rappaport understands “the Holy” in a very limited way of comprising of two main features, namely, the sacred and the numinous (290). The sacred is the speakable half of the Holy such that utterances like “God,” “Allah,” “the Buddha,” and so on, can be seen as “Ultimate Sacred Postulates,” and are the pentacle of an interconnected hierarchy of religious utterances ( 377). The numinous, in contrast, is the ineffable half of the Holy, of which nothing can properly be said. And most importantly for our case, Rappaport points out that the numinous half of the Holy has become conspicuously absent, or eroded away, from modern religions leaving only the sacred language behind (448). Again, Rappaport, as if he wanted to help me draw even tighter my analogy to Searle’s wall—the numinous is to “the wall” as God is to the border— argues that the numinous half of the Holy most likely predated language.

This crucial first sub-criteria for establishing God as an institutional fact, i.e., an epistemologically objective reality with a subjective ontology, can also be addressed from a different and less theoretical angle: The work of the archaeologist Brian Hayden, Shamans, Sorcerers, and Saints: A Prehistory of Religion (2003), provides overwhelming archaeological evidence for Hayden’s thesis that civilization has for the most part eroded “ecstatic religious experience,” away from modern life. Hayden claims, “it is precisely the earthshaking emotional experiences created in ecstatic religious rituals that were adaptive…. [as] a means of emotionally bonding people together” ( 31). Indeed, what he demonstrates in his work is that the priority of the numinous over the sacred remained virtually unchanged for hundreds of thousands of years in the prehistory of religion—which was marked by an unrestricted access to participation in religious states of consciousness—before it began to be eclipsed in the history of religion—which is also the history of religious elitism and exclusivity (147). Like Rappaport, Hayden suggests that it was the power of religious states of consciousness, or in other words, the power of participation in the numinous, to forge belief systems that override even biological survival instincts and commitments of families and clans that is largely responsible for the role that culture has now come to play in the life of the human animal (32).

However, with regard to normativity, or the second sub-criteria, the important thing here is that both Rappaport (407) and Hayden ( 44) assign an adaptive function to God, which allows us to ask, are some religions, gods, or Ultimate Sacred Postulates, better or worse than others? Obviously the answer is yes if the normative function of sanctifying, ordering, and uniting societies through the establishment of Ultimate Sacred Postulates as institutional facts is an adaptive feature of our societies. Actually, according to Hayden, ecstatic religious experience, or the numinous as Rappaport calls it, was a key adaptive feature of our species “for more that 99.5 percent of human existence,”( 22 & 31) and its demise has left us with “the book religions” as a kind of empty shell (4). But regardless of what we may think of Hayden’s characterization of religion, the evidence he provides for his thesis is also evidence that supports our claim that God is an institutional fact whose pure status function is the result of the erosion of certain mental/brain states from our modern experience, which, of course, is not to say that God is not real, but rather it is to demand that we accept and deal with the fact that God is at least as objectively real as borders and money.

Nor is it the case, as I pointed out in the introduction, that the two categories of the ontologically subjective and the ontologically objective are mutually exclusive; to establish the existence of the subjectively real ontology of God is not to deny that she might also have an objective ontology, which allows Searle to explain that, “Consciousness and intentionality, though features of the mind, are observer-independent in the sense that if I am conscious or have an intentional state such as thirst, those features do not depend for their existence on what anyone outside me thinks (94).

Thus, there is also a third ontological possibility of something having both an objective and a subjective ontology. Thirst, hunger, and, one could argue, ecstatic states of mind/brain, are all ontologically objective because they are biological states with intrinsic intentionality and they are ontologically subjective because only the experiencer can subjectively experience his or her objectively real thirst.

Thus, one could possibly argue an alternative thesis to the one stating that God is an institutional fact, proposing instead some version of the “Holy” where a real god is necessarily a union of the numinous and the sacred. One could perhaps further argue that at one time God also had an ontologically objective aspect, in the way that invisible political borders were at one time marked by visible physical barriers. In that case, we are no longer dealing with an analogy to international borders, but rather to some version of the Nietzschean idea that we have somehow killed God by eroding away its essence. Yet whatever the truth may be about God and this third possibility—maybe the union of subjective and objective ontology is all that should be meant by “the Holy”—I do not know. But one thing should be clear, for better or worse: The existence of God is an established fact.

Lastly, I feel I must say a few words about the political implications of my thinking about God as an institutional fact. My personal conclusions are hard even for myself to accept. I find them painful to admit and so I will state them succinctly and hope that I am wrong in my assessment. Basically, if God is an undeniable institutional fact necessary for the unified and coherent social body, then such a discovery spells bad news for everyone. Old-school Leftists who want to address social, political, and economic problems without acknowledging the necessary role for God to play in their humanistic solutions, will be as unhappy with the state of affairs sketched above as the to followers of the new religious Right, who will find that salvation is not assured simply because God is real. On an international scale, it is hard to imagine any Ultimate Sacred Postulate that could become real enough, as an ultimate institution fact, to hang any authentic World Order.

NOTES

It should be clear, from the perspective we are taking, that what is true of God is also true of Allah, Yahweh, and any other god whose existence is still currently an institutional fact. That is, in classrooms, courtrooms, Congress, and at Presidential inaugurations the pledges and oaths are made to the gods whose realities are still currently established as institutional facts, and not to those like Zeus or Mithra whose realities have evaporated along with the institutions that once established them.

This notion of false money as “counterfeited” is, I believe, analogous to “made up religions,” for example, the one I made up when I was a child. I could try to pass it on by converting others, but it would still be a false religion.

Rappaport lists two aspects to the Holy beside the sacred and the numinous, namely, the occult, and the divine. “The term ‘occult’ refers to religion’s peculiar efficacious capacities and the ‘divine’ will signify its spiritual referents” (Rappaport 24).

REFERENCES

Hayden, Brian.

2003 Shamans, Sorcerers, and Saints: A Prehistory of Religion. Smithsonian Books: Washington D.C.

Rappaport, Roy A.

2002 Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity. Cambridge UP: United Kingdom.

Searle, John R.

1999 Mind, Language and Society: Philosophy in the Real World. New York: Basic Books.

Thursday, March 15, 2007

Sunday, January 14, 2007

The Culture of Philosophy & The Philosophy of Culture

A Sheep In Wolf’s Clothing: Parekh, A Political Diversion.

Democracy is basically antiauthority and antiauthoritarian. It is the demand for equal say in the political process at all levels and equal participation in the socioeconomic reward system. The greatest constraint on this thrust has been liberalism, with its promise of inevitable steady betterment via rational reform. To democracy’s demand for equality now, liberalism offers hope deferred. There has been a theme not merely of the enlightened (and more powerful) half of the world establishment but even of the traditional antisystemic movements (the “Old Left”). The pillar of liberalism was the hope it offered. To the degee that the dream withers (like “a raisin in the sun”), liberalism as an ideology collapses, and the dangerous classes become dangerous once more.

– Immanuel Wallerstein

–

In The End of History, by Francis Fukuyama, I discovered a book that I loved to hate. In it, Fukuyama portrays a right-wing fantasy about how the world has finally settled on liberal democracy with its concomitant market capitalism as the best of all possible ideologies. I loved it because it was a right-wing view so divorced from the political and economic realities of this planet that it clearly demonstrated to anyone with even a cursory knowledge of Latin American and African history, for example, how the right-wing is bankrupt of moral vision. And I hated it because if one didn’t know the history of how “democracy” came to the Third World, one would assume there is no longer any need to try and come up with a system that is both politically justifiable and economically fair.

Unlike The End of History, in Bikhu Parekh’s Rethinking Multiculturalism I discovered a book that I hate to love. The reasons for my profound ambivalence toward Parekh are complex. I love most of the theory Parekh advocates. The problem is that despite appearances, and Parekh’s seeming radicalness, he is firmly committed to the economic and political status quo, and that as such his call for reform really serves more as a distraction and a diversion from the real issues that underline political and social inequality.

But before addressing the nature and future of reform, I should wake up Fukuyama and anyone else dreaming of the end of history. In looking for a less abstract account of how “liberal democracy” has been spread around the world, one can do no better than to read Noam Chomsky. Because he is more interested in practice than in theory, his work is a veritable goldmine for those interested in digging up historical details. Here are just two instances. In the first, the Guatemalan general Hector Gramajo was given a fellowship to the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard for his contribution to Central American liberal democracy. Chomsky notes that in a Harvard International Review interview Mr. Gramajo explains: “We have created a more humanitarian, less costly strategy, to be more compatible with the democratic system. We instituted civil affairs [in 1982] which provides development for 70 percent of the population, while we kill 30 percent. Before, the strategy was to kill 100 percent”—an obvious improvement (qt. in Year 501 29). In the second, the Reagonites were able quietly to explain the natural benefit of liberal democracy to the peoples of Angola and Mozambique with a cost of only “$60 billion dollars in damage and 1.5 million deaths from 1980 to 1988” (qt. in Year 501 29). One sees that reading Chomsky is like listening to a loud alarm clock, because according to those dreaming along with Fukuyama, the fact that both Guatemala and Angola are now embracing “liberal” democracy proves the natural appeal of capitalism. Also, it is very important to note the quotation marks around “liberal”—as in “liberal” democracy—lest we forget that non-market economic models were, prior to Washington’s “persuasive” arguments, overwhelmingly popular. But before we look closer at the interaction between “liberal” democracy and capitalism we need to address the issue closer at hand: What to make of Parekh’s call for reform?

The reasons for my profound ambivalence toward Parekh are complex. I love most of what Parekh advocates: for example, the need to recognize that humans are culturally embedded creatures; that dialogue is the only way to solve cross-cultural conflicts; that such conflicts are always contextual; and that cultures hold within them representations of “the good life” that can’t be legitimately ignored or undermined from the outside. Furthermore, his idea of “pluralist universalism” being a view that yields a prescription of the good life is attractive because it takes into account the differences and particularities of people in such a way as to allow one to advocate for a certain minimum standard of universal human rights. But most admirably, Parekh consistently maintains that “minimum universal values” will still need to be interpreted, prioritized, and adopted to differing cultural contexts, and reconciled in cases of conflicting views. That is, where there is a disagreement all we can do is ask for rational justifications and continue to press for change when we remain unconvinced that some cultural practice is not in violation of the minimum standards. From these ideas I gather that Parekh would not accept the killing of 30% of Guatemalans as a reasonable means of persuasion. Still, I would like Parekh’s ideas even better if they came with an explicit condemnation of violence as a means of conflict resolution. Since violence can be so affective and is so readily available to the powerful unless it is made politically and practically (covert violence is still violence) unacceptable, it is hard to see where the motivation will come from to talk through difficult problems and reach complex solutions that meet the standards of universal minimum values.

From the above descriptions, we can already begin to see there are two sides to Parekh’s work. There is a theoretical side, and a practical side. The theoretical side is what I really enjoy about Rethinking Multiculturalism, and the practical side is what I find implausible and distracting. The key to understanding the theoretical lies in understanding the interaction of human nature with human culture. I will take a closer look at this side shortly. The key to understanding the practical side—the side that advocates rewriting national constitutions and passing laws that apply only to some segments of the society, i.e. those whose particular cultural needs are not being addressed by the one-law-fits-all approach—is understanding that he is not at all interested in looking for the economic reasons for social conflict. But outside the ivory tower the concern is not differences of culture, but differences of income—and derivatively of political power as distributed across social classes. In other words, it is economic unfairness and not cultural differences that fuels the greatest social conflicts, and that is in need of the greatest reform. But before I spell out what’s wrong with Rethinking Multiculturalism, I should say more specifically what is right about it.

Parekh’s discussion of human nature is an important contribution to our understanding of ourselves us cultural creatures. Although he explicitly eschews cultural relativism as a fact that needs to be a part of any account of our species as social beings, his work effectively demonstrates that cultural relativism is indeed a reality. His views on multiculturalism are predicated on precisely the fact that no single individual from any one particular cultural viewpoint can legitimately pass judgment on someone of another culture without first coming to some understanding of the moral and ontological assumptions embedded in that culture. The resulting cross-cultural evaluation will then be a reflection of “our” values juxtaposed against “theirs” in a way that the pragmatic concerns for what has been agreed upon as minimal moral values are brought to the forefront and used as a standard for mutual evaluation of each other. In such conflict-resolution approaches, the emphasis is placed on advocating a persuasive interpretation of the minimal values as a means of prescribing universally accepted moral standards.

Specifically, Parekh describes culture as that which lies between the universal and the particular in human beings. What is universal (e.g., our biology) acquires—and is mediated by—different meanings that are associated with it by what is particular to any given culture. And likewise, what is particular to a culture (those things that distinguish one culture from another) are related to each other by virtue of being equally embedded in and limited by what is universal (e.g., our biology and existential conditions). This means that human beings are neither completely opaque nor completely transparent to each other.

Moreover, the relationship between biology and culture is not static for Parekh. Indeed, by joining the two concepts he yields what I believe is actually the most radical conclusion of the whole book. He writes that, “human nature does not exhaust all that characterizes human beings” (118). There is also the human condition to take into account, and as active participants in evolution we are in a dialectic with nature, which shapes us. Furthermore, this dialectic has created a situation where

… nature has been so deeply shaped by layers of social influences… [that] we cannot easily detach what is natural from what is manmade or social…. [In short] cultures are not superstructures built upon identical and unchanging foundations…but unique human creations…[that in turn] gives rise to different kinds of human beings. (122)

Parekh never actually proves this point nor does he ever spell out what the “different kinds of human beings” are. Nevertheless, like cultural relativism generally, I find it intuitively appealing for political reasons and not scientific ones—it is inherently unprovable and metaphorical in nature—because it forces us to consider the ontological status of cultural differences on an equal par with similarities. Such an understanding allows us to evade both the biological determinism and the cultural determinism of naturalists like Montesquieu and culturalists like Herder. Also, by embracing both the universality and the particularity of people and cultures we acknowledge an obligation to respond to different people and cultures more holistically.

However, the danger of believing in “different kinds of human beings” is that someone might come along and argue that some kinds of humans are more important than others, and that is why the idea of cultural relativism is so appealing to me. In effect, cultural relativism states that if one culture is valuable then all cultures are valuable. There are real differences between cultures that simply can’t be theorized coherently because the very notion of coherence only has meaning from a consistent set of cultural values. Multiculturalism is itself such a set of liberal cultural values. It can be pragmatically applied to actual cultural conflicts, but cannot yield any meta-view on the inherent worth of culture as such.

For that reason, the value of Parekh’s work lies in its attempt to theorize from an academic perspective on the practical consequences of cultural relativism. But Parekh denies the role that the assumption of cultural relativism plays in his formulation of “pluralist universalism,” and in doing so he misses the value of his own work.

The problem with Parekh is that he wants to use his understanding of multiculturalism as a foundation for sweeping political reforms that, one, are not really that sweeping; two, are completely unrealistic and impractical; and three, the advocacy of which can only serve as a distraction from the serious problems of the failure of “liberal” democracy more generally. Indeed, judging from the examples that Parekh uses as cases of injustice—Rushdie, turbans, circumcision, etc—the world situation would seem to be in pretty good shape. I don’t mean to imply that his examples are not real concerns for real people, but only that judging from the radicalness of Parekh’s prescription one might be led to assume that those are the greatest ills facing our generation. But given the fact that Parekh is so reform-minded that he is willing to completely rewrite national constitutions so as to be more flexible, and our legal system so as to undo the inherent inequality that results when we treat people with different histories and cultures “equally,” one would think he wouldn’t shy away from addressing some of the unfair ways that our economic and political system are manifest in contemporary societies. But instead of trying to make the existing political system work more fairly, he chooses to advocate for the much more radical idea that the systems and centers of authority should be multiple and local; and that sovereignty should be shared both intra-nationally and inter-nationally through “cross-border” political organizations. These are views that I can’t fathom being possible to implement or make functional, and hence I can’t take them or him seriously as a reformer. Parekh makes recommendations that can’t possibly be put into practice under the existing socio-economic structures, and hence his whole project risks confusing the issues and making the work of more serious-minded reformers harder.

From the fact that he is an economist and a reformer—who is not an economic reformer—one can only draw the conclusion that he is satisfied with the economic system. In effect, his ideas about how to reform society presuppose that a functioning economic and political system is already in place. That false assumption is precisely the starting point for real political reformers.

Serious reformers realize that there are two large impediments to social change. The first is the unfair concentration of the world’s wealth and the monopolization of the world’s resources by the wealthy. The second is a political and social system that protects the wealthy from democratic forces. Consider, for example, what one would rationally expect from a free democratic system. In a democracy, where people vote along their own economic interests, one would expect a situation in which wealth is not heavily concentrated in the hands of a very few. In other words, if everyone votes to increase their own share of the economic spoils, then, given that no one person’s vote is worth more than another, no one would be able to take possession of those spoils to the disproportionate degree that we find in contemporary life. But democracy is not working as one would expect, as Michael Parenti demonstrates when he explains the findings of the economist, Paul Krugman, in his article, “The Super Rich Are Out of Sight.” In it, Parenti explains why the wealthiest people, “go uncounted in most income distribution reports.” He also provides statistics on income distribution:

…not only have the top 20 percent grown more affluent compared with everyone one below, the top 5 percent have grown richer compared with the next 15 percent. The top one percent have become richer compared with the next 4 percent. And the top 0.25 percent have grown richer than the next 0.75 percent. That top 0.25 percent owns more wealth than the other 99 percent combined.

Given that over 80% of the American population believe, “the economic system is ‘inherently unfair,’ and that working people have too little say in what goes on in the country” (Profit Over People 55), the need for an explanation becomes pressing for the reformer.

Such an explanation for economic inequality is to be found in the political and social arenas. Politically the explanation, and focal point for the reformer, comes by looking at where the democratic system is being distorted, i.e. the electoral process. Consider the impact of these figures on elections: “In US electoral politics…the richest one-quarter of one percent [0.25%] of Americans make 80% of all individual political contributions and corporations outspend labor by a margin of 10 – 1” (Profit Over People 11). From these figures one can see, as I argued in class, that our political system—our most important public resource and institution—has been in effect privatized. With political and hence economic decision-making priced out of reach of the vast majority of people one comes to understand who exactly our representatives are representing.

However, if the political system is protecting the economic system, we have still to ask what is protecting the political system? After all, we do live in a democracy. For the answer to that question we have to look at three sectors of society more closely, the public relations experts, the news media, and the ivory tower.

First let’s consider the experts. Noam Chomsky quotes Edward Bernays, Walter Lippmann, Harold Lasswell, and Reinhold Niebuhr, some of the most powerful figures in public relations. Chomsky begins with what Bernays wrote in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science:

‘The very essence of the democratic process’ is ‘the freedom to persuade and suggest,’ what [Bernays] calls ‘the engineering of consent.’ ‘A leader,’ he continues, ‘frequently cannot wait for the people to arrive at even general understanding… Democratic leaders must play their part in…engineering…consent to socially constructive goals and values,’ applying ‘scientific principles and tried practices to the task of getting people to support ideas and programs.’….Similar ideas are standard across the political spectrum…. The dean of U.S. journalists, Walter Lippmann, described a ‘revolution’ in ‘the practice of democracy’ as ‘the manufacture of consent’ has become ‘a self-conscious art and a regular organ of popular government’ …. later, Harold Lasswell explained in the Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences that we should not succumb to ‘democratic dogmatisms about men being the best judges of their own interests.’ ….When social arrangements deny [the rulers] the requisite force to compel obedience, it is necessary to turn to ‘a whole new technique of control, largely through propaganda’ because of the ‘ignorance and superstition [of]…the masses.’ In the same year, Reinhold Niebuhr argued that ‘rationality belongs to the cool observers,’ while ‘the proletarian’ follows not reason but faith, based upon a crucial element of ‘necessary illusion.’ …Niebuhr urged that those he addressed…recognize ‘the stupidity of the average man’ and provide the ‘emotionally potent oversimplification’ required to keep the proletarian on course to create a new society. (Necessary Illusions 18).

Knowing the history of the public relations industry not only goes a long way to understanding how the majority in a democracy allows 0.25% of the wealthiest to own almost everything, but it also gives us some context for Samuel Huntington’s seemingly bizarre advice in American Politics (1981): “The architects of power in the United States must create a force that can be felt but not seen. Power remains strong when it remains in the dark; exposed to the sunlight it begins to evaporate.” And while pointing out the function of the so-called communist threat (today he would call it the terrorist threat), Huntington adds, “You may have to sell [intervention or other military action] in such a way as to create the mis-impression that it is the Soviet Union (read Al-Quaida) that you are fighting. That is what the United States has been doing ever since the Truman Doctrine” (Profit Over People 140).

For those of my readers who might be wondering, “If all this is true, why haven’t we heard more about it?” we need only turn to the second part of the initial question of what is protecting the political system as it protects the economic system? In other words it is time to look more closely at the news media.

First of all it is important to note that just as the concentration of wealth has been increasing, the concentration of the media has followed suit. In 1982, 50 media firms controlled almost all forms of the mass media. In 1990, that number had gone down to 23 firms. In 2002 we were down to 9—Disney, AOL Time Warner, Viacom, News Corporation, Bertelsmann, General Electric, Sony, AT&T-Liberty Media, and Vivendi Universal. Today, only 6 transnational conglomerates control and own almost everything . (Manufacturing Consent xiii).

Traditionally the function of a free news media has been that of “watch dog.” Its role in a democracy is to keep our leaders honest by being free to report the news unfiltered by the demands of the powerful. But this role is in direct conflict with the media’s status as a group of for-profit organizations that are owned by the people that own the country and the political system—that 0.25%. That is to say, despite the mythology of the reporter as “watch dog” the fact is they are working for the rulers and not the ruled. In other words, “the major media—particularly, the elite media that set the agenda that others generally follow—are corporations ‘selling’ privileged audiences to other businesses. It would hardly come as a surprise if the picture of the world they present were to reflect the perspectives and interests of the sellers, the buyers, and the product” (Necessary Illusions 8). For those interested in a more precise analysis of how the media shape our world view I suggest reading Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky’s monumental work on the subject, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. But for the purpose of this paper it suffices to briefly mention the five filters that Herman and Chomsky determined that information must pass through.

• Only the very rich can set up and run major news outlets.

• Advertising revenue determines the success of the news producers.

• “The source of much news is determined by government and corporate organizations, which may have many thousand of employees dedicated to providing appropriate material” (Smith 200).

• The ability of corporate-supported Think Tanks and organizations to produce “flak,” the negative and costly reactions of the populace against the media for being too “liberal.”

• The ideological filter, namely, the ability to exclude views by labeling them communist—or in today’s world—sympathetic to terrorists.

Aside from the public relations industry and the media, the third and last shield that protects the massive economic inequality that is ultimately responsible for most of the social and cultural conflicts both inside and outside the United States is the education system, from which people like Parekh protect the economic and political systems by pursuing “reforms” that leave the real structure of domination and control untouched while feeding us utopian fantasies.

Institutes of higher education have their own complex systems of filters, not too unlike those of the media. Noam Chomsky, who is a real reformer as well as an “Institute Professor” at M.I.T.—meaning that he is qualified to teach in any department—gives us an insider’s view:

…it’s extremely important that there not be a field that studies these questions [on the political economy of democracies]—because if there ever were such a field, people might come to understand too much, and in a relatively free society like ours, they might start to do something with that understanding. Well, no institution is going to encourage that. I mean, there’s nothing in what I just said that you couldn’t explain to junior high school students, it’s all pretty straightforward. But it’s not what you study in a junior high school Civics course—what you study there is propaganda about the way systems are supposed to work but don’t.

Incidentally, part of the genius of this aspect of the higher education system is that it can get people to sell out even while they think they’re doing exactly the right thing. So some young person going into academia will say to themselves, “Look, I’m going to be a real radical here”—and you can be, as long as you adapt yourself to these categories which guarantee that you’ll never ask the right questions, and that you’ll never even look at the right questions. But you don’t feel like you’re selling out, you’re not saying “I’m working for the ruling class” or anything like that—you’re not, you’re being a Marxist economist or something. But the effect is, they’ve totally neutralized you. (Understanding Power 242)

One can almost see Parekh think, “I’m being a real radical here.” But my purpose is not to pick on Parekh, with whose ideas I almost always agreed. My purpose is to draw us back away from the distraction that his ideas pose and to the real issues facing any serious reformer.

Sri Aurobindo, the great Indian yogi, philosophy, poet, and a leader of the nationalist independence movement, wrote that there are only two possibilities for the future political unification of the world. The first is that of, “the control of the enormous mass of mankind by an oligarchy,” but he warns that this, “would lead to an unnatural suppression of great natural and moral forces and in the end a tremendous disorder, perhaps a world shattering explosion” (Aurobindo 407). The other possibility is:

…the ideal of unification of mankind [that] would be a system in which, as first rule of common and harmonious life, the human peoples would be allowed to form their own groupings according to their natural divisions of locality, race, culture, economic convenience and not according to the more violent accidents of history or the egoistic will of powerful nations whose policy it must always be to compel the smaller or less timely organized to serve their interests as dependents or obey their commands as subjects. (Aurobindo 406).

In other words, either we work for a situation where the rich and powerful nations continue to dominate at the expense of the poor and weak ones—half of the world’s population continues to live on less than $2 a day. Or, we give up the goal of global domination and work to establish an international body of democratically elected law makers. This is what it means in today’s Global Village to be an advocate of democracy.

The situation is getting increasingly grim. The figures listed about it are especially horrifying when looked at from a global perspective: That the “top 0.25 percent owns more wealth [in the United States] than the other 99 percent combined” is doubly distressing when one considers that, as is often noted, the resource distribution of the world from the point of view of a village of 100 people would mean that six of them (all from the United States) would own 60% of the world’s wealth. Those “six people” are probably the same 0.25% of Americans who own more than 99% of the rest of the population. No wonder the rich want to surround themselves with Star Wars—to keep the have-nots away.

Actually, according to Immanuel Wallerstein, the founder of economic world-systems analysis , the third-world has had enough. Among a long list of problems facing liberal democracies because of the economic unfairness that capitalism perpetuates, he gives us warnings about “North-South” conflicts: “Even more serious, who will limit North-South little wars, not only initiated, but deliberately initiated, not by the North but by the South, as part of a long-term strategy of military confrontation? The [first] Gulf War was the beginning, not the end, of this process. The United States won the war, it is said. But at what price?” (Wallerstein 451).

Whatever the answer, one can see three things: one, history is far from ending; two, Parekh is beside the point; and three, any real solution to our very serious social problems will have to come from taking an honest look at those aspects of our economic and political system that are fueling them. We have good systems already in place, we just need to make them work the way they were intended. As long as our leaders continue to be bought, and our corporations shielded from market forces, the populations of the world will continue to pay for the free market.

Works Cited

Aurobindo, Sri. The Human Cycle; The Ideal of Human Unity; War and Self-Determination. 7th ed. Pondicherry, India: Sri Aurobindo Ashram, 1997.

Chomsky, Noam. Year 501: The Conquest Continues. Boston: South End, 1993.

---. Deterring Democracy. NewYork: Hill and Wang, 1997.

---. Necessary Illusions: Thought Control in Democratic Societies. Boston: South End, 1989.

---. Profit Over People: Neoliberalism and Global Order. New York: Seven Stories, 1999.

---. Understanding Power: The Indispensible Chomsky. Eds. Peter R. Mitchell and John Schoeffel. New York: The New Press, 2002.

Herman, Edward S. and Noam Chomsky. Manufacturing Concent: The Political Econmy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon, 2002.

Parekh, Bhikhu. Rethinking Multiculturalism: Cultural Diversity and Political Theory. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2000.

Parenti, Michael. “The Super Rich are Out of Sight.” Michael Parenti Political Archive. January 2000. 7 June 2004.

Smith, Neil. Chomsky: Ideas and Ideals. Cambridge, England: Campbridge UP, 2000.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. The Essential Wallerstein. New York: New Press, 2000.

Democracy is basically antiauthority and antiauthoritarian. It is the demand for equal say in the political process at all levels and equal participation in the socioeconomic reward system. The greatest constraint on this thrust has been liberalism, with its promise of inevitable steady betterment via rational reform. To democracy’s demand for equality now, liberalism offers hope deferred. There has been a theme not merely of the enlightened (and more powerful) half of the world establishment but even of the traditional antisystemic movements (the “Old Left”). The pillar of liberalism was the hope it offered. To the degee that the dream withers (like “a raisin in the sun”), liberalism as an ideology collapses, and the dangerous classes become dangerous once more.

– Immanuel Wallerstein

–

In The End of History, by Francis Fukuyama, I discovered a book that I loved to hate. In it, Fukuyama portrays a right-wing fantasy about how the world has finally settled on liberal democracy with its concomitant market capitalism as the best of all possible ideologies. I loved it because it was a right-wing view so divorced from the political and economic realities of this planet that it clearly demonstrated to anyone with even a cursory knowledge of Latin American and African history, for example, how the right-wing is bankrupt of moral vision. And I hated it because if one didn’t know the history of how “democracy” came to the Third World, one would assume there is no longer any need to try and come up with a system that is both politically justifiable and economically fair.

Unlike The End of History, in Bikhu Parekh’s Rethinking Multiculturalism I discovered a book that I hate to love. The reasons for my profound ambivalence toward Parekh are complex. I love most of the theory Parekh advocates. The problem is that despite appearances, and Parekh’s seeming radicalness, he is firmly committed to the economic and political status quo, and that as such his call for reform really serves more as a distraction and a diversion from the real issues that underline political and social inequality.

But before addressing the nature and future of reform, I should wake up Fukuyama and anyone else dreaming of the end of history. In looking for a less abstract account of how “liberal democracy” has been spread around the world, one can do no better than to read Noam Chomsky. Because he is more interested in practice than in theory, his work is a veritable goldmine for those interested in digging up historical details. Here are just two instances. In the first, the Guatemalan general Hector Gramajo was given a fellowship to the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard for his contribution to Central American liberal democracy. Chomsky notes that in a Harvard International Review interview Mr. Gramajo explains: “We have created a more humanitarian, less costly strategy, to be more compatible with the democratic system. We instituted civil affairs [in 1982] which provides development for 70 percent of the population, while we kill 30 percent. Before, the strategy was to kill 100 percent”—an obvious improvement (qt. in Year 501 29). In the second, the Reagonites were able quietly to explain the natural benefit of liberal democracy to the peoples of Angola and Mozambique with a cost of only “$60 billion dollars in damage and 1.5 million deaths from 1980 to 1988” (qt. in Year 501 29). One sees that reading Chomsky is like listening to a loud alarm clock, because according to those dreaming along with Fukuyama, the fact that both Guatemala and Angola are now embracing “liberal” democracy proves the natural appeal of capitalism. Also, it is very important to note the quotation marks around “liberal”—as in “liberal” democracy—lest we forget that non-market economic models were, prior to Washington’s “persuasive” arguments, overwhelmingly popular. But before we look closer at the interaction between “liberal” democracy and capitalism we need to address the issue closer at hand: What to make of Parekh’s call for reform?

The reasons for my profound ambivalence toward Parekh are complex. I love most of what Parekh advocates: for example, the need to recognize that humans are culturally embedded creatures; that dialogue is the only way to solve cross-cultural conflicts; that such conflicts are always contextual; and that cultures hold within them representations of “the good life” that can’t be legitimately ignored or undermined from the outside. Furthermore, his idea of “pluralist universalism” being a view that yields a prescription of the good life is attractive because it takes into account the differences and particularities of people in such a way as to allow one to advocate for a certain minimum standard of universal human rights. But most admirably, Parekh consistently maintains that “minimum universal values” will still need to be interpreted, prioritized, and adopted to differing cultural contexts, and reconciled in cases of conflicting views. That is, where there is a disagreement all we can do is ask for rational justifications and continue to press for change when we remain unconvinced that some cultural practice is not in violation of the minimum standards. From these ideas I gather that Parekh would not accept the killing of 30% of Guatemalans as a reasonable means of persuasion. Still, I would like Parekh’s ideas even better if they came with an explicit condemnation of violence as a means of conflict resolution. Since violence can be so affective and is so readily available to the powerful unless it is made politically and practically (covert violence is still violence) unacceptable, it is hard to see where the motivation will come from to talk through difficult problems and reach complex solutions that meet the standards of universal minimum values.

From the above descriptions, we can already begin to see there are two sides to Parekh’s work. There is a theoretical side, and a practical side. The theoretical side is what I really enjoy about Rethinking Multiculturalism, and the practical side is what I find implausible and distracting. The key to understanding the theoretical lies in understanding the interaction of human nature with human culture. I will take a closer look at this side shortly. The key to understanding the practical side—the side that advocates rewriting national constitutions and passing laws that apply only to some segments of the society, i.e. those whose particular cultural needs are not being addressed by the one-law-fits-all approach—is understanding that he is not at all interested in looking for the economic reasons for social conflict. But outside the ivory tower the concern is not differences of culture, but differences of income—and derivatively of political power as distributed across social classes. In other words, it is economic unfairness and not cultural differences that fuels the greatest social conflicts, and that is in need of the greatest reform. But before I spell out what’s wrong with Rethinking Multiculturalism, I should say more specifically what is right about it.

Parekh’s discussion of human nature is an important contribution to our understanding of ourselves us cultural creatures. Although he explicitly eschews cultural relativism as a fact that needs to be a part of any account of our species as social beings, his work effectively demonstrates that cultural relativism is indeed a reality. His views on multiculturalism are predicated on precisely the fact that no single individual from any one particular cultural viewpoint can legitimately pass judgment on someone of another culture without first coming to some understanding of the moral and ontological assumptions embedded in that culture. The resulting cross-cultural evaluation will then be a reflection of “our” values juxtaposed against “theirs” in a way that the pragmatic concerns for what has been agreed upon as minimal moral values are brought to the forefront and used as a standard for mutual evaluation of each other. In such conflict-resolution approaches, the emphasis is placed on advocating a persuasive interpretation of the minimal values as a means of prescribing universally accepted moral standards.

Specifically, Parekh describes culture as that which lies between the universal and the particular in human beings. What is universal (e.g., our biology) acquires—and is mediated by—different meanings that are associated with it by what is particular to any given culture. And likewise, what is particular to a culture (those things that distinguish one culture from another) are related to each other by virtue of being equally embedded in and limited by what is universal (e.g., our biology and existential conditions). This means that human beings are neither completely opaque nor completely transparent to each other.

Moreover, the relationship between biology and culture is not static for Parekh. Indeed, by joining the two concepts he yields what I believe is actually the most radical conclusion of the whole book. He writes that, “human nature does not exhaust all that characterizes human beings” (118). There is also the human condition to take into account, and as active participants in evolution we are in a dialectic with nature, which shapes us. Furthermore, this dialectic has created a situation where

… nature has been so deeply shaped by layers of social influences… [that] we cannot easily detach what is natural from what is manmade or social…. [In short] cultures are not superstructures built upon identical and unchanging foundations…but unique human creations…[that in turn] gives rise to different kinds of human beings. (122)

Parekh never actually proves this point nor does he ever spell out what the “different kinds of human beings” are. Nevertheless, like cultural relativism generally, I find it intuitively appealing for political reasons and not scientific ones—it is inherently unprovable and metaphorical in nature—because it forces us to consider the ontological status of cultural differences on an equal par with similarities. Such an understanding allows us to evade both the biological determinism and the cultural determinism of naturalists like Montesquieu and culturalists like Herder. Also, by embracing both the universality and the particularity of people and cultures we acknowledge an obligation to respond to different people and cultures more holistically.

However, the danger of believing in “different kinds of human beings” is that someone might come along and argue that some kinds of humans are more important than others, and that is why the idea of cultural relativism is so appealing to me. In effect, cultural relativism states that if one culture is valuable then all cultures are valuable. There are real differences between cultures that simply can’t be theorized coherently because the very notion of coherence only has meaning from a consistent set of cultural values. Multiculturalism is itself such a set of liberal cultural values. It can be pragmatically applied to actual cultural conflicts, but cannot yield any meta-view on the inherent worth of culture as such.

For that reason, the value of Parekh’s work lies in its attempt to theorize from an academic perspective on the practical consequences of cultural relativism. But Parekh denies the role that the assumption of cultural relativism plays in his formulation of “pluralist universalism,” and in doing so he misses the value of his own work.

The problem with Parekh is that he wants to use his understanding of multiculturalism as a foundation for sweeping political reforms that, one, are not really that sweeping; two, are completely unrealistic and impractical; and three, the advocacy of which can only serve as a distraction from the serious problems of the failure of “liberal” democracy more generally. Indeed, judging from the examples that Parekh uses as cases of injustice—Rushdie, turbans, circumcision, etc—the world situation would seem to be in pretty good shape. I don’t mean to imply that his examples are not real concerns for real people, but only that judging from the radicalness of Parekh’s prescription one might be led to assume that those are the greatest ills facing our generation. But given the fact that Parekh is so reform-minded that he is willing to completely rewrite national constitutions so as to be more flexible, and our legal system so as to undo the inherent inequality that results when we treat people with different histories and cultures “equally,” one would think he wouldn’t shy away from addressing some of the unfair ways that our economic and political system are manifest in contemporary societies. But instead of trying to make the existing political system work more fairly, he chooses to advocate for the much more radical idea that the systems and centers of authority should be multiple and local; and that sovereignty should be shared both intra-nationally and inter-nationally through “cross-border” political organizations. These are views that I can’t fathom being possible to implement or make functional, and hence I can’t take them or him seriously as a reformer. Parekh makes recommendations that can’t possibly be put into practice under the existing socio-economic structures, and hence his whole project risks confusing the issues and making the work of more serious-minded reformers harder.

From the fact that he is an economist and a reformer—who is not an economic reformer—one can only draw the conclusion that he is satisfied with the economic system. In effect, his ideas about how to reform society presuppose that a functioning economic and political system is already in place. That false assumption is precisely the starting point for real political reformers.

Serious reformers realize that there are two large impediments to social change. The first is the unfair concentration of the world’s wealth and the monopolization of the world’s resources by the wealthy. The second is a political and social system that protects the wealthy from democratic forces. Consider, for example, what one would rationally expect from a free democratic system. In a democracy, where people vote along their own economic interests, one would expect a situation in which wealth is not heavily concentrated in the hands of a very few. In other words, if everyone votes to increase their own share of the economic spoils, then, given that no one person’s vote is worth more than another, no one would be able to take possession of those spoils to the disproportionate degree that we find in contemporary life. But democracy is not working as one would expect, as Michael Parenti demonstrates when he explains the findings of the economist, Paul Krugman, in his article, “The Super Rich Are Out of Sight.” In it, Parenti explains why the wealthiest people, “go uncounted in most income distribution reports.” He also provides statistics on income distribution:

…not only have the top 20 percent grown more affluent compared with everyone one below, the top 5 percent have grown richer compared with the next 15 percent. The top one percent have become richer compared with the next 4 percent. And the top 0.25 percent have grown richer than the next 0.75 percent. That top 0.25 percent owns more wealth than the other 99 percent combined.

Given that over 80% of the American population believe, “the economic system is ‘inherently unfair,’ and that working people have too little say in what goes on in the country” (Profit Over People 55), the need for an explanation becomes pressing for the reformer.

Such an explanation for economic inequality is to be found in the political and social arenas. Politically the explanation, and focal point for the reformer, comes by looking at where the democratic system is being distorted, i.e. the electoral process. Consider the impact of these figures on elections: “In US electoral politics…the richest one-quarter of one percent [0.25%] of Americans make 80% of all individual political contributions and corporations outspend labor by a margin of 10 – 1” (Profit Over People 11). From these figures one can see, as I argued in class, that our political system—our most important public resource and institution—has been in effect privatized. With political and hence economic decision-making priced out of reach of the vast majority of people one comes to understand who exactly our representatives are representing.

However, if the political system is protecting the economic system, we have still to ask what is protecting the political system? After all, we do live in a democracy. For the answer to that question we have to look at three sectors of society more closely, the public relations experts, the news media, and the ivory tower.

First let’s consider the experts. Noam Chomsky quotes Edward Bernays, Walter Lippmann, Harold Lasswell, and Reinhold Niebuhr, some of the most powerful figures in public relations. Chomsky begins with what Bernays wrote in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science:

‘The very essence of the democratic process’ is ‘the freedom to persuade and suggest,’ what [Bernays] calls ‘the engineering of consent.’ ‘A leader,’ he continues, ‘frequently cannot wait for the people to arrive at even general understanding… Democratic leaders must play their part in…engineering…consent to socially constructive goals and values,’ applying ‘scientific principles and tried practices to the task of getting people to support ideas and programs.’….Similar ideas are standard across the political spectrum…. The dean of U.S. journalists, Walter Lippmann, described a ‘revolution’ in ‘the practice of democracy’ as ‘the manufacture of consent’ has become ‘a self-conscious art and a regular organ of popular government’ …. later, Harold Lasswell explained in the Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences that we should not succumb to ‘democratic dogmatisms about men being the best judges of their own interests.’ ….When social arrangements deny [the rulers] the requisite force to compel obedience, it is necessary to turn to ‘a whole new technique of control, largely through propaganda’ because of the ‘ignorance and superstition [of]…the masses.’ In the same year, Reinhold Niebuhr argued that ‘rationality belongs to the cool observers,’ while ‘the proletarian’ follows not reason but faith, based upon a crucial element of ‘necessary illusion.’ …Niebuhr urged that those he addressed…recognize ‘the stupidity of the average man’ and provide the ‘emotionally potent oversimplification’ required to keep the proletarian on course to create a new society. (Necessary Illusions 18).

Knowing the history of the public relations industry not only goes a long way to understanding how the majority in a democracy allows 0.25% of the wealthiest to own almost everything, but it also gives us some context for Samuel Huntington’s seemingly bizarre advice in American Politics (1981): “The architects of power in the United States must create a force that can be felt but not seen. Power remains strong when it remains in the dark; exposed to the sunlight it begins to evaporate.” And while pointing out the function of the so-called communist threat (today he would call it the terrorist threat), Huntington adds, “You may have to sell [intervention or other military action] in such a way as to create the mis-impression that it is the Soviet Union (read Al-Quaida) that you are fighting. That is what the United States has been doing ever since the Truman Doctrine” (Profit Over People 140).

For those of my readers who might be wondering, “If all this is true, why haven’t we heard more about it?” we need only turn to the second part of the initial question of what is protecting the political system as it protects the economic system? In other words it is time to look more closely at the news media.

First of all it is important to note that just as the concentration of wealth has been increasing, the concentration of the media has followed suit. In 1982, 50 media firms controlled almost all forms of the mass media. In 1990, that number had gone down to 23 firms. In 2002 we were down to 9—Disney, AOL Time Warner, Viacom, News Corporation, Bertelsmann, General Electric, Sony, AT&T-Liberty Media, and Vivendi Universal. Today, only 6 transnational conglomerates control and own almost everything . (Manufacturing Consent xiii).

Traditionally the function of a free news media has been that of “watch dog.” Its role in a democracy is to keep our leaders honest by being free to report the news unfiltered by the demands of the powerful. But this role is in direct conflict with the media’s status as a group of for-profit organizations that are owned by the people that own the country and the political system—that 0.25%. That is to say, despite the mythology of the reporter as “watch dog” the fact is they are working for the rulers and not the ruled. In other words, “the major media—particularly, the elite media that set the agenda that others generally follow—are corporations ‘selling’ privileged audiences to other businesses. It would hardly come as a surprise if the picture of the world they present were to reflect the perspectives and interests of the sellers, the buyers, and the product” (Necessary Illusions 8). For those interested in a more precise analysis of how the media shape our world view I suggest reading Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky’s monumental work on the subject, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. But for the purpose of this paper it suffices to briefly mention the five filters that Herman and Chomsky determined that information must pass through.

• Only the very rich can set up and run major news outlets.

• Advertising revenue determines the success of the news producers.

• “The source of much news is determined by government and corporate organizations, which may have many thousand of employees dedicated to providing appropriate material” (Smith 200).

• The ability of corporate-supported Think Tanks and organizations to produce “flak,” the negative and costly reactions of the populace against the media for being too “liberal.”

• The ideological filter, namely, the ability to exclude views by labeling them communist—or in today’s world—sympathetic to terrorists.

Aside from the public relations industry and the media, the third and last shield that protects the massive economic inequality that is ultimately responsible for most of the social and cultural conflicts both inside and outside the United States is the education system, from which people like Parekh protect the economic and political systems by pursuing “reforms” that leave the real structure of domination and control untouched while feeding us utopian fantasies.

Institutes of higher education have their own complex systems of filters, not too unlike those of the media. Noam Chomsky, who is a real reformer as well as an “Institute Professor” at M.I.T.—meaning that he is qualified to teach in any department—gives us an insider’s view:

…it’s extremely important that there not be a field that studies these questions [on the political economy of democracies]—because if there ever were such a field, people might come to understand too much, and in a relatively free society like ours, they might start to do something with that understanding. Well, no institution is going to encourage that. I mean, there’s nothing in what I just said that you couldn’t explain to junior high school students, it’s all pretty straightforward. But it’s not what you study in a junior high school Civics course—what you study there is propaganda about the way systems are supposed to work but don’t.

Incidentally, part of the genius of this aspect of the higher education system is that it can get people to sell out even while they think they’re doing exactly the right thing. So some young person going into academia will say to themselves, “Look, I’m going to be a real radical here”—and you can be, as long as you adapt yourself to these categories which guarantee that you’ll never ask the right questions, and that you’ll never even look at the right questions. But you don’t feel like you’re selling out, you’re not saying “I’m working for the ruling class” or anything like that—you’re not, you’re being a Marxist economist or something. But the effect is, they’ve totally neutralized you. (Understanding Power 242)

One can almost see Parekh think, “I’m being a real radical here.” But my purpose is not to pick on Parekh, with whose ideas I almost always agreed. My purpose is to draw us back away from the distraction that his ideas pose and to the real issues facing any serious reformer.

Sri Aurobindo, the great Indian yogi, philosophy, poet, and a leader of the nationalist independence movement, wrote that there are only two possibilities for the future political unification of the world. The first is that of, “the control of the enormous mass of mankind by an oligarchy,” but he warns that this, “would lead to an unnatural suppression of great natural and moral forces and in the end a tremendous disorder, perhaps a world shattering explosion” (Aurobindo 407). The other possibility is:

…the ideal of unification of mankind [that] would be a system in which, as first rule of common and harmonious life, the human peoples would be allowed to form their own groupings according to their natural divisions of locality, race, culture, economic convenience and not according to the more violent accidents of history or the egoistic will of powerful nations whose policy it must always be to compel the smaller or less timely organized to serve their interests as dependents or obey their commands as subjects. (Aurobindo 406).

In other words, either we work for a situation where the rich and powerful nations continue to dominate at the expense of the poor and weak ones—half of the world’s population continues to live on less than $2 a day. Or, we give up the goal of global domination and work to establish an international body of democratically elected law makers. This is what it means in today’s Global Village to be an advocate of democracy.

The situation is getting increasingly grim. The figures listed about it are especially horrifying when looked at from a global perspective: That the “top 0.25 percent owns more wealth [in the United States] than the other 99 percent combined” is doubly distressing when one considers that, as is often noted, the resource distribution of the world from the point of view of a village of 100 people would mean that six of them (all from the United States) would own 60% of the world’s wealth. Those “six people” are probably the same 0.25% of Americans who own more than 99% of the rest of the population. No wonder the rich want to surround themselves with Star Wars—to keep the have-nots away.

Actually, according to Immanuel Wallerstein, the founder of economic world-systems analysis , the third-world has had enough. Among a long list of problems facing liberal democracies because of the economic unfairness that capitalism perpetuates, he gives us warnings about “North-South” conflicts: “Even more serious, who will limit North-South little wars, not only initiated, but deliberately initiated, not by the North but by the South, as part of a long-term strategy of military confrontation? The [first] Gulf War was the beginning, not the end, of this process. The United States won the war, it is said. But at what price?” (Wallerstein 451).

Whatever the answer, one can see three things: one, history is far from ending; two, Parekh is beside the point; and three, any real solution to our very serious social problems will have to come from taking an honest look at those aspects of our economic and political system that are fueling them. We have good systems already in place, we just need to make them work the way they were intended. As long as our leaders continue to be bought, and our corporations shielded from market forces, the populations of the world will continue to pay for the free market.

Works Cited

Aurobindo, Sri. The Human Cycle; The Ideal of Human Unity; War and Self-Determination. 7th ed. Pondicherry, India: Sri Aurobindo Ashram, 1997.

Chomsky, Noam. Year 501: The Conquest Continues. Boston: South End, 1993.

---. Deterring Democracy. NewYork: Hill and Wang, 1997.

---. Necessary Illusions: Thought Control in Democratic Societies. Boston: South End, 1989.

---. Profit Over People: Neoliberalism and Global Order. New York: Seven Stories, 1999.

---. Understanding Power: The Indispensible Chomsky. Eds. Peter R. Mitchell and John Schoeffel. New York: The New Press, 2002.